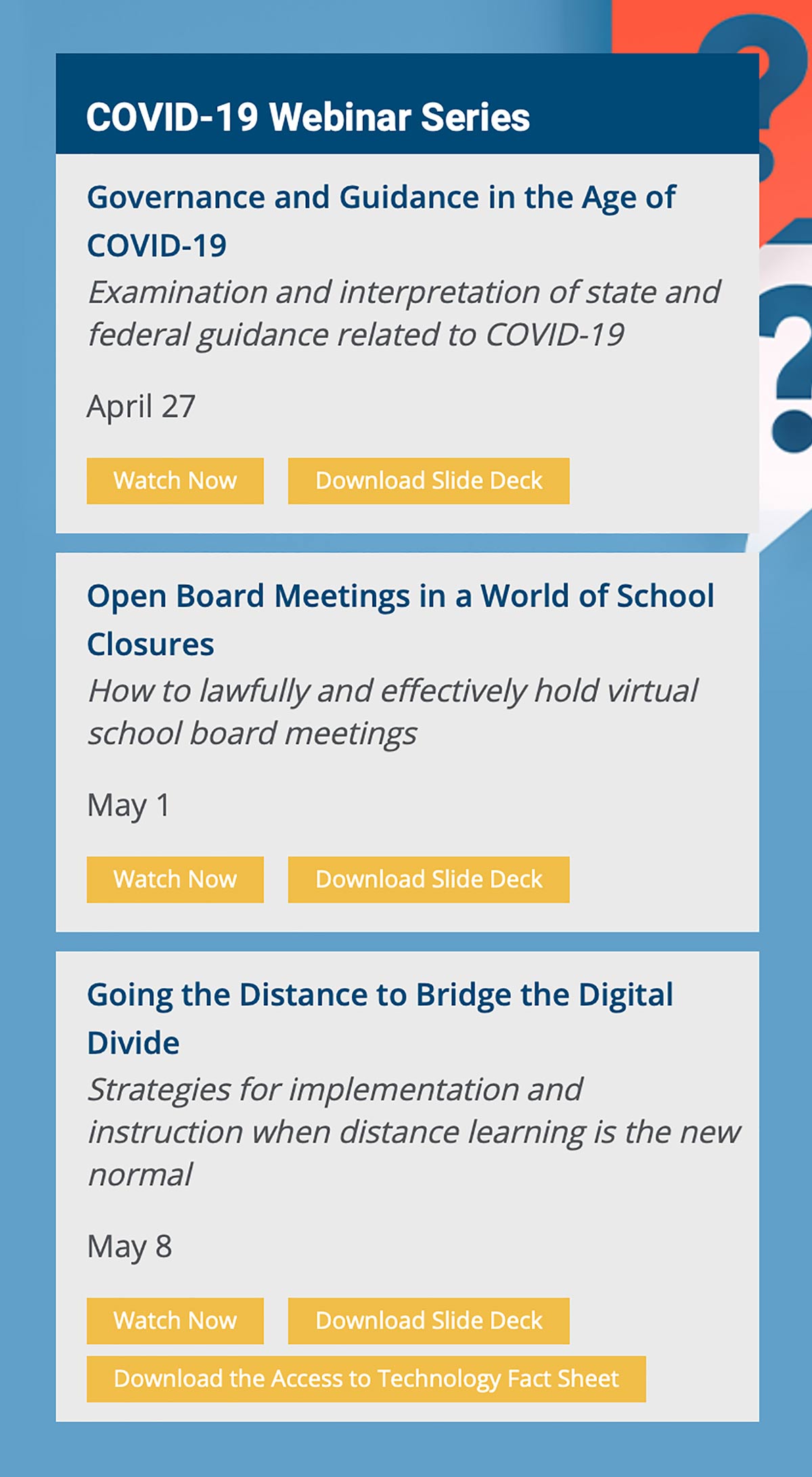

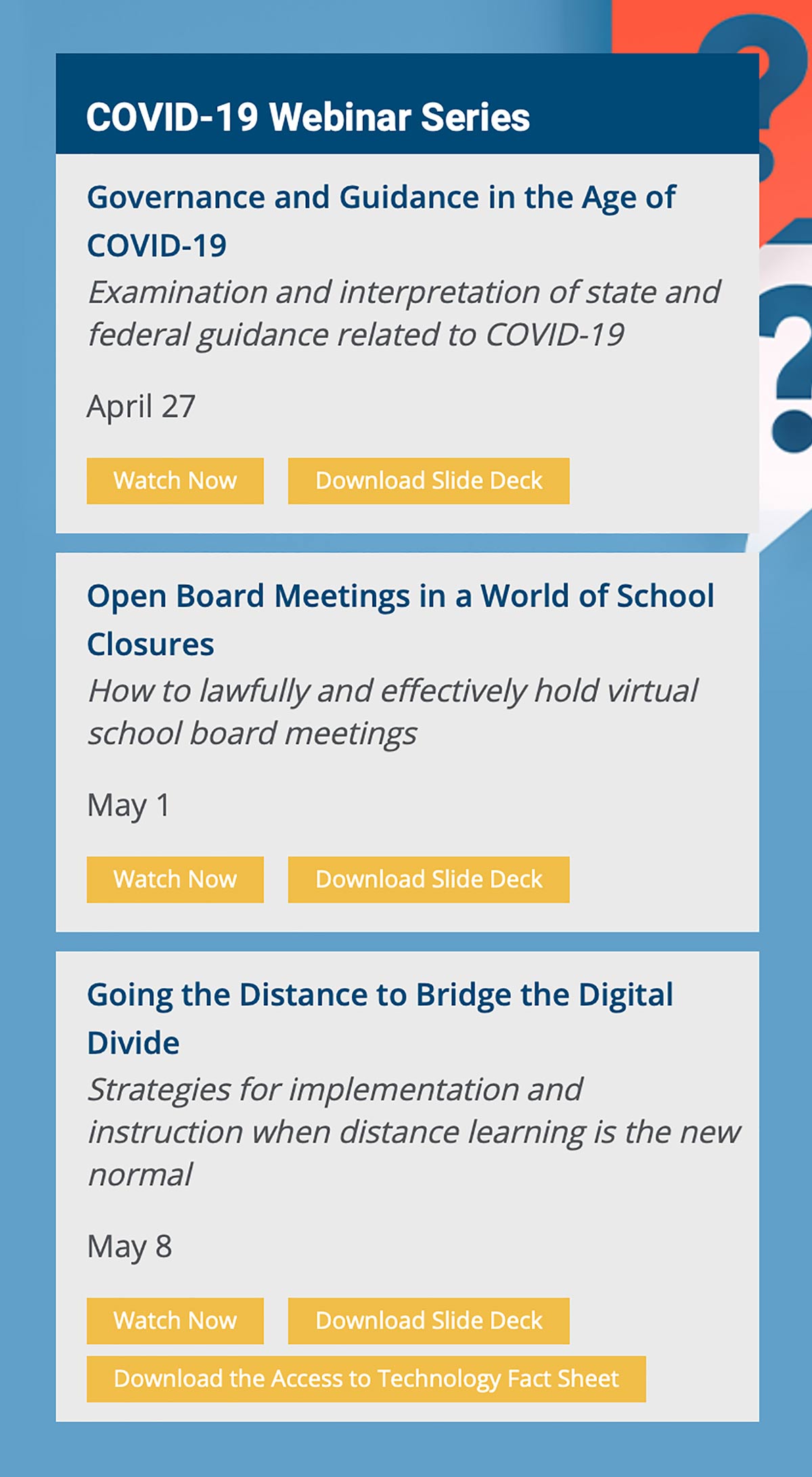

How to conduct a virtual meeting of the board

Waivers provided by Gov. Newsom’s executive orders allow board members to meet via telephone or livestream from separate locations. The board does not need to make space available for the public to appear, board members do not need to publicly disclose their location, and boards do not need a quorum of members to participate from locations within the boundaries of the district.

How to conduct a virtual meeting of the board

Waivers provided by Gov. Newsom’s executive orders allow board members to meet via telephone or livestream from separate locations. The board does not need to make space available for the public to appear, board members do not need to publicly disclose their location, and boards do not need a quorum of members to participate from locations within the boundaries of the district.

William Tunick of Dannis Woliver Kelley emphasized the importance of having a plan in place if one or more board members experiences technical difficulties and gets cut out of the meeting, or if the meeting platform goes down. Panelists agreed in the case that the viewing platform is not streaming, the meeting should be paused to ensure transparency.

An additional key aspect to think about in a virtual meeting is the transition between open session and closed session. The board must receive public comment about closed session items before going into closed session. Tunick recommended that separate meeting links (or a separate phone number), or even separate livestreaming platforms, be used to ensure that the session is indeed closed once comment is received.

Accepting public comment in a virtual meeting

LEA boards have several options with respect to gathering and airing public comment in a virtual board meeting. Mike Smith, a founding partner of Lozano Smith, said it is important to use plain language in the meeting agenda when describing how to provide public comment. Boards should let the public know how they will be taking comment — via email, voicemail or live comment during the meeting — and provide the time of the meeting, the platform it will be on and contact information (including any relevant email address, web link or phone number to submit public comment). “I think our agenda notices have actually got to be more detailed and have more information in them than prior to the pandemic,” Smith said.

No matter the method, boards should keep in mind that the time constraints in place prior to the pandemic may remain in place. For example, many boards may choose to limit public comment to 3 minutes per person, and 20 minutes per topic.

For meetings soliciting public comment via email, Smith reviewed practical details that should be included in the meeting agenda. He said it is helpful if the email identifies the agenda item it is addressing in the subject line, and that a separate email is sent for each agenda item if a member of the public wishes to comment on more than one. Another consideration is the length of the email versus the time allotted for public comment in a meeting.

Smith, along with other panelists, recommended posting the agenda before the 72-hour window and noting that public comment will be accepted through a particular time on the day prior to the meeting. That will give a designated person (either on the board or staff) time to read through comments, sort them into categories and organize them in a way that will allow a designated person at the meeting to read through them.

Smith warned that it is important during this time to remember that the Brown Act allows for public criticism. “When you are deciding which email comments to read, if you have an excess of comments, make sure you read them in a neutral, non-discriminatory way that is not based on the content of the person’s speech,” said Smith.

- Good-faith efforts to educate and serve students with disabilities, despite the limitations presented by physical distancing, will both more fully benefit the student and help shield the LEA from possible legal action or administrative disputes.

- Creating a thorough compliance record detailing all services and resources provided to students with disabilities is critical for accountability and transparency during distance learning.

- Individual Education Program services should be thoughtfully considered and reasonably calculated for a child to make progress on goals through distance learning. Even more dramatically than in a classroom setting, what works for one student may not work for another, panelists said. Parents or guardians are a key part of this process.

- Outside of a few minor changes from the California Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Education, the bulk of guidance about special education and COVID-19 is not binding, but rather recommendations.

- Now realizing the vast possibilities for instructional methods, LEAs must actively prepare for what special education services may look like next school year and beyond.

The U.S. Department of Education has said it will seek no waivers to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and outlined core principles for which individualized education must occur for all students, including those with disabilities. The big question for districts, however, is that if distance learning is the only option, should they be penalized if students do not meet the goals on their IEPs? “It’s hard to answer that question,” said Ron Wenkart, partner at Atkinson, Andelson, Loya, Ruud and Romo. “We’ll just have to wait and see what the courts do and what the hearing officers do.”

Considering the limitations placed on many special education services through a remote format, Wenkart and Kathryn Meola, CSBA’s Chief Legal Counsel and Director of the Education Legal Alliance, said well-meaning efforts to meet IDEA and Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) requirements will serve LEAs well.