This enrollment data is the first look at changes in essential student categories that occurred throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. California follows the national trend in enrollment declines and, in some categories, surpasses it. Early analysis of this data shows remarkable enrollment decreases among some of the state’s most vulnerable students. These drops raise red flags about whether local educational agencies are genuinely accounting for these students and if the historic infusion of education funding is going where it is needed the most. Two of the more notable drops occurred with kindergarteners and students experiencing homelessness.

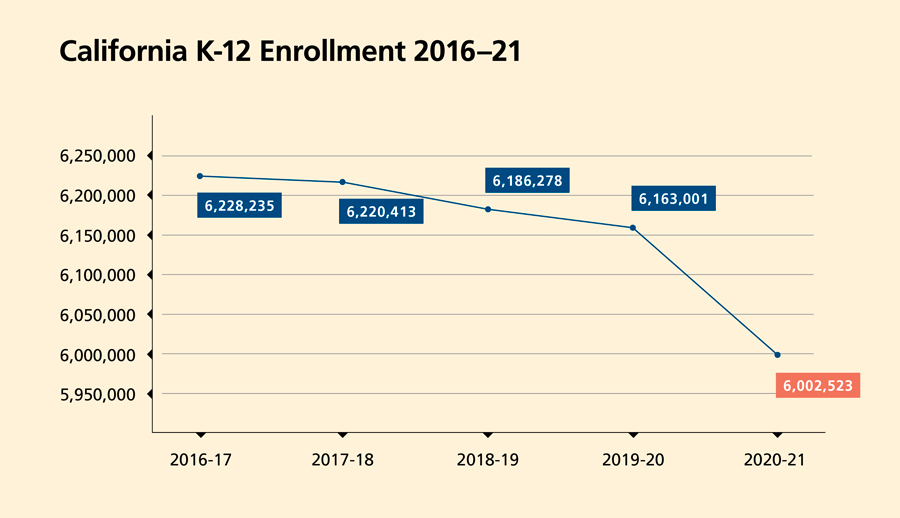

California experienced a nearly 3 percent decline in overall enrollment (160,478 fewer students) from 2019–20 to 2020–21. This marks the most significant year-over-year decrease in enrollment in the past 20 years and far outpaced the state’s projections before the pandemic. There was also a 3 percent decline in the number of socioeconomically disadvantaged students. Given the increased economic hardships of the pandemic, it is somewhat unclear why this number substantially declined. However, it is a significant trend to monitor once federal and state COVID-19 assistance decreases. The most substantial in enrollment occurred with kindergarten students. The 12 percent drop from 2019–20 to 2020–21 represents over 60,000 fewer kindergarten students enrolled from the previous year, surpassing the national average decline of 9 percent.

According to the New York Times, nationally, the most severe reductions occurred in lower-income urban school districts, which is consistent with the situation in California. The Public Policy Institute of California found a more considerable drop in the state’s kindergarten enrollment for students from lower-income backgrounds (13 percent) versus students from non-low-income backgrounds (9 percent). This phenomenon has caused concern around the potential for a “kindergarten surge” in the coming school years, which may provide districts with challenges around staffing, facility use and resource allocation as state and federal emergency aid dries up.

While it would be reassuring if these numbers reflect a significant reduction in homelessness, there are compelling reasons to be skeptical of that conclusion. Before the pandemic, a 2018 state audit found that California schools had undercounted students who lacked stable housing by 37 percent, or nearly 100,000 students. Furthermore, the pandemic presented school districts with new obstacles in communicating with students and families. Combined with the demonstrated economic stressors on families who were already housing insecure, such steep declines raise the real possibility that undercounting students may persist. Failure to identify students experiencing homelessness is not a simple bureaucratic glitch. Undercounting students who lack stable housing means that a vulnerable population may miss out on invaluable instructional time and funding for critical services such as social services, transportation and counseling.

School board members can ask what enrollment trends look like in their districts among different student populations. Identifying unique enrollment patterns will help plan for current services with the incoming state and federal funding surge. Those patterns will also help board members prepare for future academic years where emergency aid might not be available. In both instances, board members should pay particular attention to student populations with whom economic hardship makes inclusive engagement logistically challenging. Those students’ access to essential educational supports will depend on it.