chool districts must provide all students with the quality education and support they need to meet their potential and be ready for college, career and civic life. To help meet this challenge, education leaders should focus on the needs of students that have been historically underserved, including students with disabilities.

What does this mean for district governance teams? First, governance team members must understand the special education landscape. To help, CSBA released The Landscape of Special Education in California: A Primer for Board Members in May 2019 and continues to advocate for increased resources through its Full and Fair Funding initiative. Learning about best practices can help trustees and superintendents ask informed questions about local programs and support investments that are shown to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. With accurate information in hand, governance teams can make decisions to ensure equity, transparency and accountability in the education provided to all students.

- Students with disabilities learn best in the least restrictive environment and contribute to the educational experiences of their peers. Board members should ensure that students with disabilities are educated with peers without disabilities to the maximum extent appropriate (called the least restrictive environment, or LRE). This is not only a legal requirement, but student outcomes are correlated with the amount of time students spend in the LRE. However, districts and county offices of education must still provide students with disabilities with the necessary supports to ensure access to the instructional content.

When children attend public schools, they are not just learning academic skills, but also learning about the world around them. Students benefit when they learn how to interact and collaborate with peers from different backgrounds. Therefore, the diversity of the school system is an asset, and the inclusion of students with disabilities enriches the education of all students.

- All students are considered general education students first. While students with disabilities require additional supports, accommodations and resources, they should be considered general education students first. In fact, by 2014, almost two-thirds of U.S. students with disabilities were spending 80 percent or more of their instructional days in general education settings. Therefore, all school staff must have the training and support to meet the needs of students with disabilities. Two main challenges facing districts are the lack of qualified special education teachers and the lack of overall preparation and support for all teachers to serve their students with disabilities, discussed further in focus area 3.

- Both general and special education teachers need professional learning opportunities. Insufficient professional development is cited as one of the main reasons why special education teachers leave the profession. And given that most students with disabilities receive the bulk of their instruction from general education teachers, it is important that teacher preparation and professional learning opportunities incorporate information that is tailored to educating students with disabilities.

Board members should ensure that their district invests in recruitment and preparation for special education teachers and that professional development for all teachers includes a focus on meeting the needs of students with disabilities. Fortunately, California’s new 2019–20 budget provides $5 million in Educator Workforce Investment Grants focused on professional development related to special education and inclusive practices. Given the current shortage of special education teachers in most districts, recruitment and retention both require the attention of governance teams.

- Early intervention is critical. Access to early intervention for students, starting from birth, can greatly improve outcomes and ensure that their needs are met before falling behind in school. Early and appropriate intervention, treatment and support have been proven to significantly lessen the long-term effects of a developmental delay, and sometimes can even resolve initial concerns. Within districts, this can mean that preschool and kindergarten programs can play a key role in identifying student needs and addressing them. For a board, this goes back to ensuring that their district’s preschool, kindergarten and other staff receive the appropriate support and training to identify and meet the needs of students. This is an area that received plenty of attention from Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature, leading to the inclusion of $492.7 million in California’s 2019–20 budget to be allocated to districts based on the number of 3- to 5-year-old children with disabilities they serve.

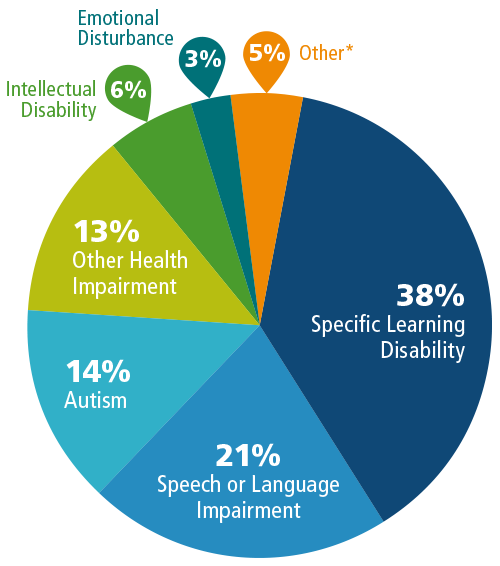

Source: California Department of Education DataQuest

Over the past 10 years (from 2007–08 to 2017–18), the number of students identified for special education services has increased by 96,761 students. During this same period, both the number and percentage of students identified with autism and other health impairments has more than doubled, while the identification of students with a specific learning disability and speech or language impairment has dropped. There are several possible explanations for shifts in identification over time, but some of these changes could be explained — at least in part — by reclassification of students as physicians, families and educators become more knowledgeable about specific disabilities. For example, a student who in the past might have been classified as having a severe intellectual disability or emotional disturbance might now be classified as having autism.