his past January, educators across the state (and nation) were fixated on the Los Angeles Unified School District’s six-day teacher’s strike. The LAUSD strike was followed almost immediately by a seven-day work stoppage in Oakland and a highly publicized one-day walkout for Sacramento USD teachers on April 11.

These bargaining conflicts in some of California’s largest urban school districts are representative of the funding crisis looming large in districts across the state. The undeniable fact is that these strikes — and threats of others possibly to come — are occurring because of decades of underinvestment in our public schools, and because the Legislature often views the Proposition 98 school funding formula as a ceiling versus a floor for funding.

In essence, the state has been “shorting” our schools and our students of the funding that they deserve — and it is a “big short.” While California’s economy and state general fund revenues have been growing at a steady pace, it has recently been noted by several of my colleagues that schools in California have been experiencing a “silent recession.” While this recession may have been “silent” for the general public, CSBA has been sounding the alarm about our burgeoning education funding crisis for more than a decade.

We have consistently challenged the Legislature and every governor to fund the actual costs to educate our students and operate our schools. We have consistently lobbied the Legislature and publicized the fact that the annual barrage of new unfunded mandates, increased operating costs (utilities, health care, etc.) and chronic underfunding means our education system cannot fully meet its charge without severely compromising the level of services provided to our students.

Source: Ed Week (2014)

This became abundantly clear when the dust settled in LAUSD and a more complex and urgent reality emerged about what “more money” looks like. The publicly available summary of the deal that United Teachers Los Angeles struck with the district included, in part, a class size reduction for grades four through 12 of four students per classroom by 2021–22, an increase in the availability of nurses in every school and more counselors and librarians in all secondary schools, development of an English learner master plan and campus green spaces.

To the surprise of no one, it didn’t take long for the question to arise of whether the agreement is financially tenable for the district moving forward — a question that likely will still be hotly debated long after you read this article. With that said, the underlying takeaway from this strike and others is that our current funding model for public education is simply not providing the level of funding needed to meet the needs of our schools. Whether you’re in Los Angeles County or Siskiyou County, our schools need and deserve more resources.

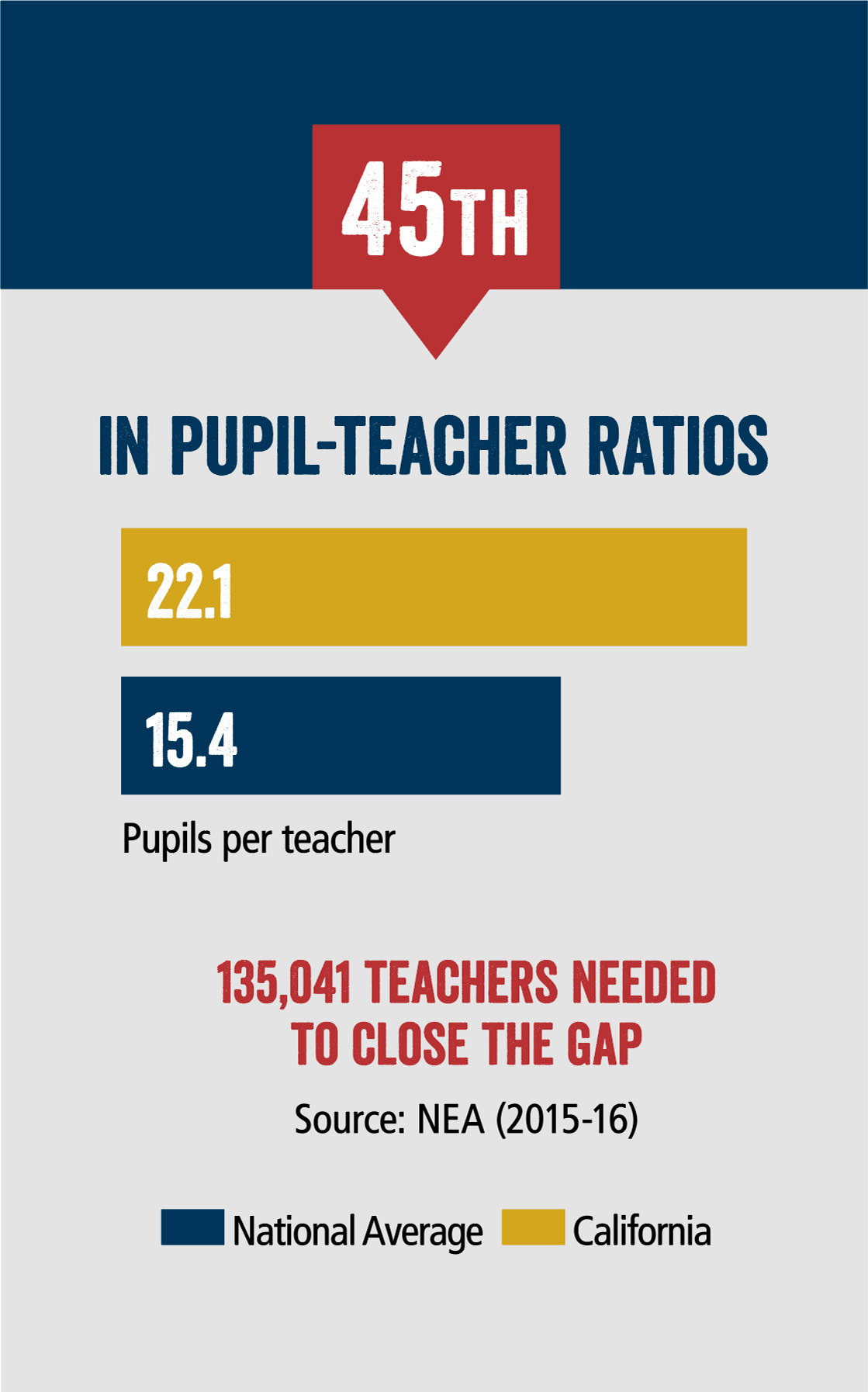

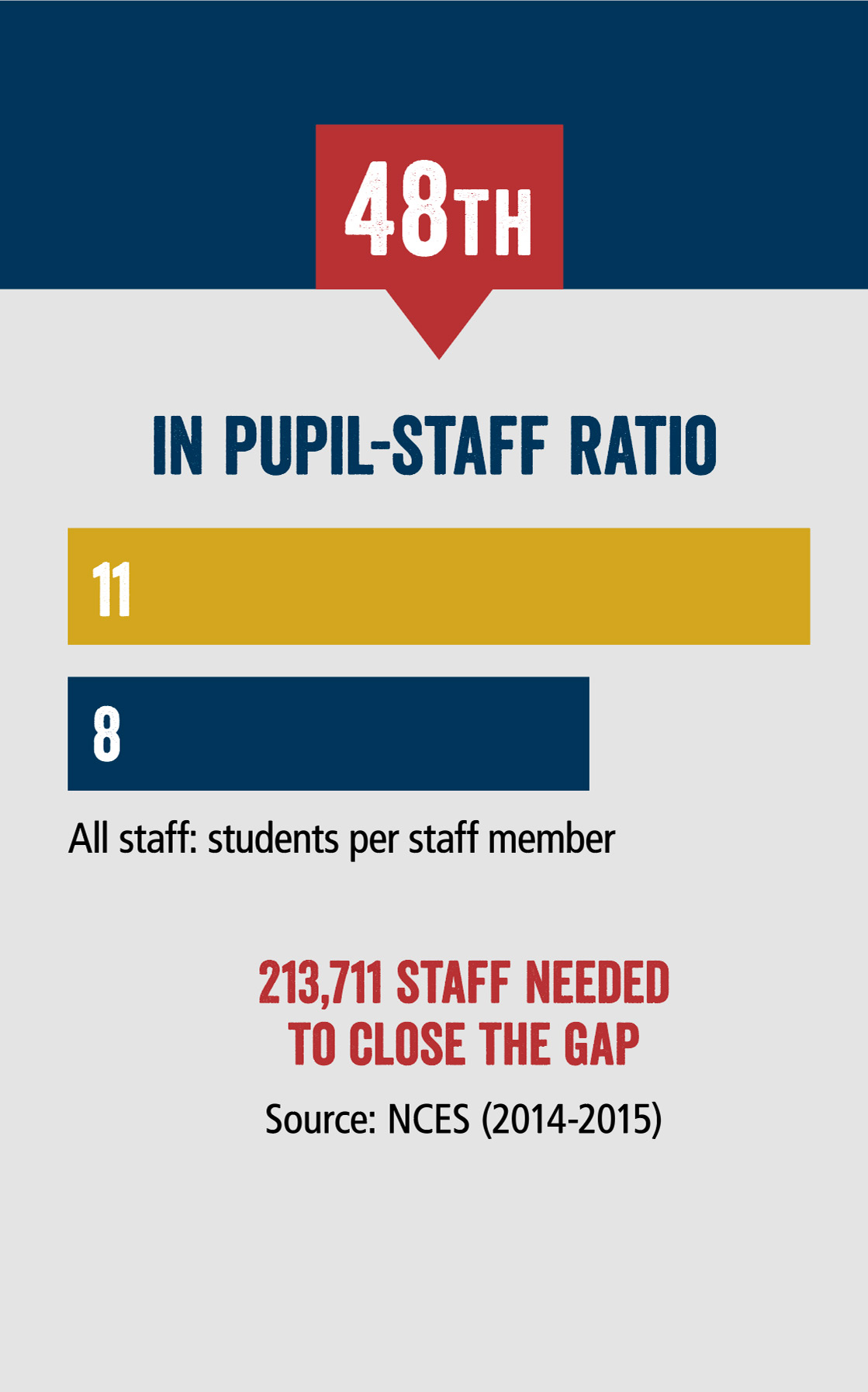

California boasts the fifth-largest economy in the world and the largest gross domestic product of any state, yet we languish near the bottom of every measure of school funding and school staffing. The state ranks 41st in the number of instructional aides per student, 45th in student–teacher ratio, 45th in student–administrator ratio, 46th in student–principal ratio, 48th in student–counselor ratio, 48th in overall student–staff ratio and 50th in student–librarian ratio.

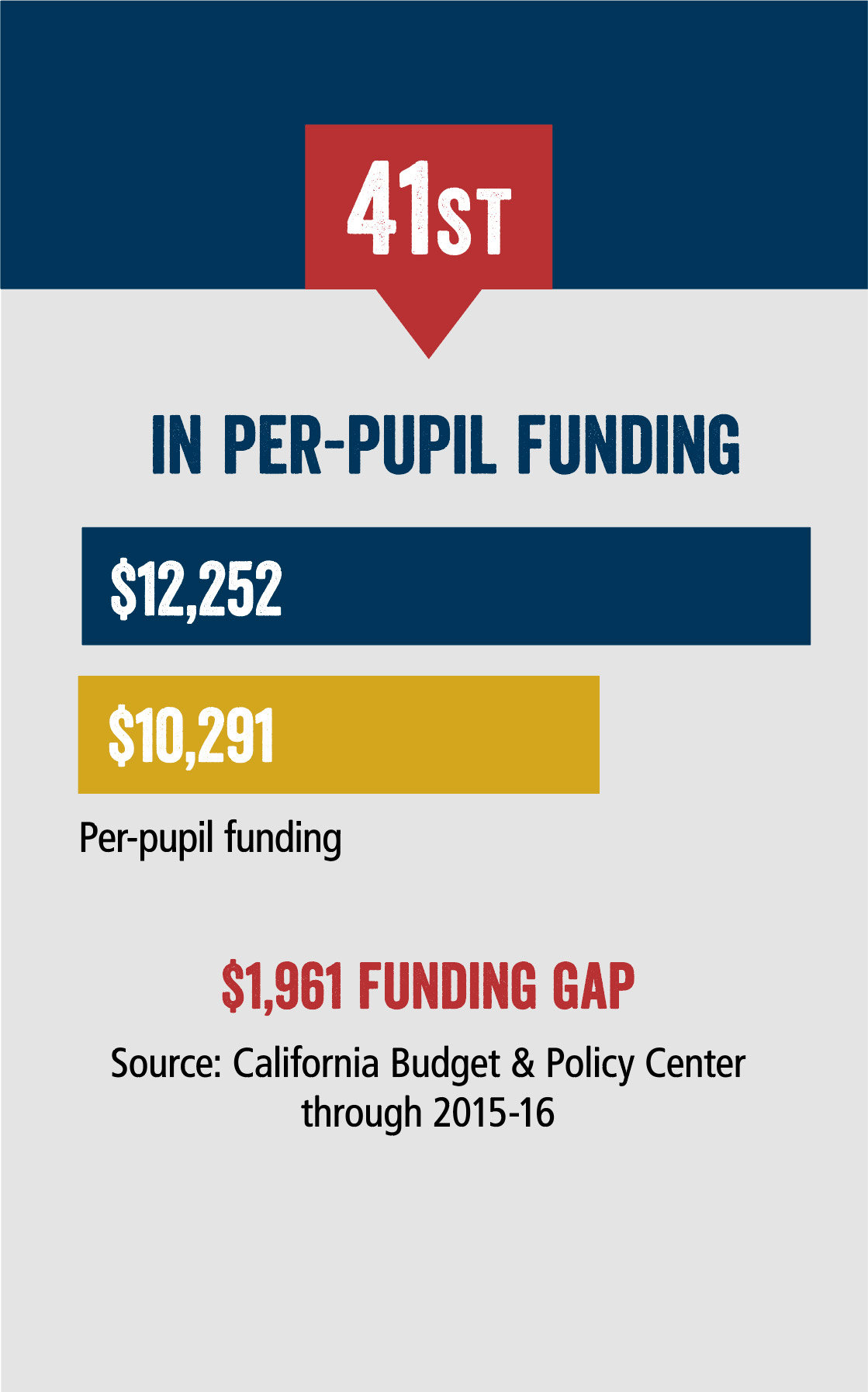

Overall, California ranks a paltry 41st — and no higher than 38th — in multiple education per-pupil funding analyses, and yet across the state, our teachers, administrators and school leaders are constantly being asked to do more with less. Oakland USD Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell expressed this very point and the frustration many education professionals feel in a letter to district parents just prior to the teachers’ union strike vote, stating that, “As both a former teacher and former principal, I understand the frustration of being asked to do so much with so little.”

Our teachers, school staff, administrators and elected leaders have a rightful expectation that the sweat and tears they pour into their work should be matched with the resources they need to provide every student with a quality education.

California’s teachers, staff and school leaders are as talented and creative as they are tenacious and resilient, but it is a pure fantasy to expect that those working the hardest to educate our students will be able to pull our state out of the bottom tier in results if we remain in the bottom tier of funding.

The bottom tier is exactly the opposite of how Proposition 98 was originally written. The law states that “no transfer or allocation of funds pursuant to this section shall be required at any time that the Director of Finance and the Superintendent of Public Instruction mutually determine that current annual expenditures per student equal or exceed the average annual expenditure per student of the ten states with the highest annual expenditures per student.” What that says, quite directly, is that Proposition 98 was designed to get California to the top 10 nationally in per-pupil funding.

If that sounds familiar, it should. This is the crux of CSBA’s Full and Fair Funding effort, calling on the Legislature to raise education funding in California to the national average in per-pupil funding by 2020 and into the top 10 nationally by 2025.

In L.A., Oakland, Sacramento and in every corner of the state, the “more money” conversation is one that will not go away until we are willing to invest in our public schools in a way that is truly conducive to student success — nothing less than the future of our children, our communities and our state hangs in the balance.

Governor Gavin Newsom said as much in his February State of the State address, proclaiming that “something needs to change — we need to have an honest conversation about how we fund our schools at a state and local level.”

We agree with the Governor, and would argue that not only is such a conversation long overdue, but needs to be accompanied by a real investment that matches actual student needs with actual funding. Anything less than that will continue to be a “big short” for our students and for the future of our great state.