in the time of

coronavirus

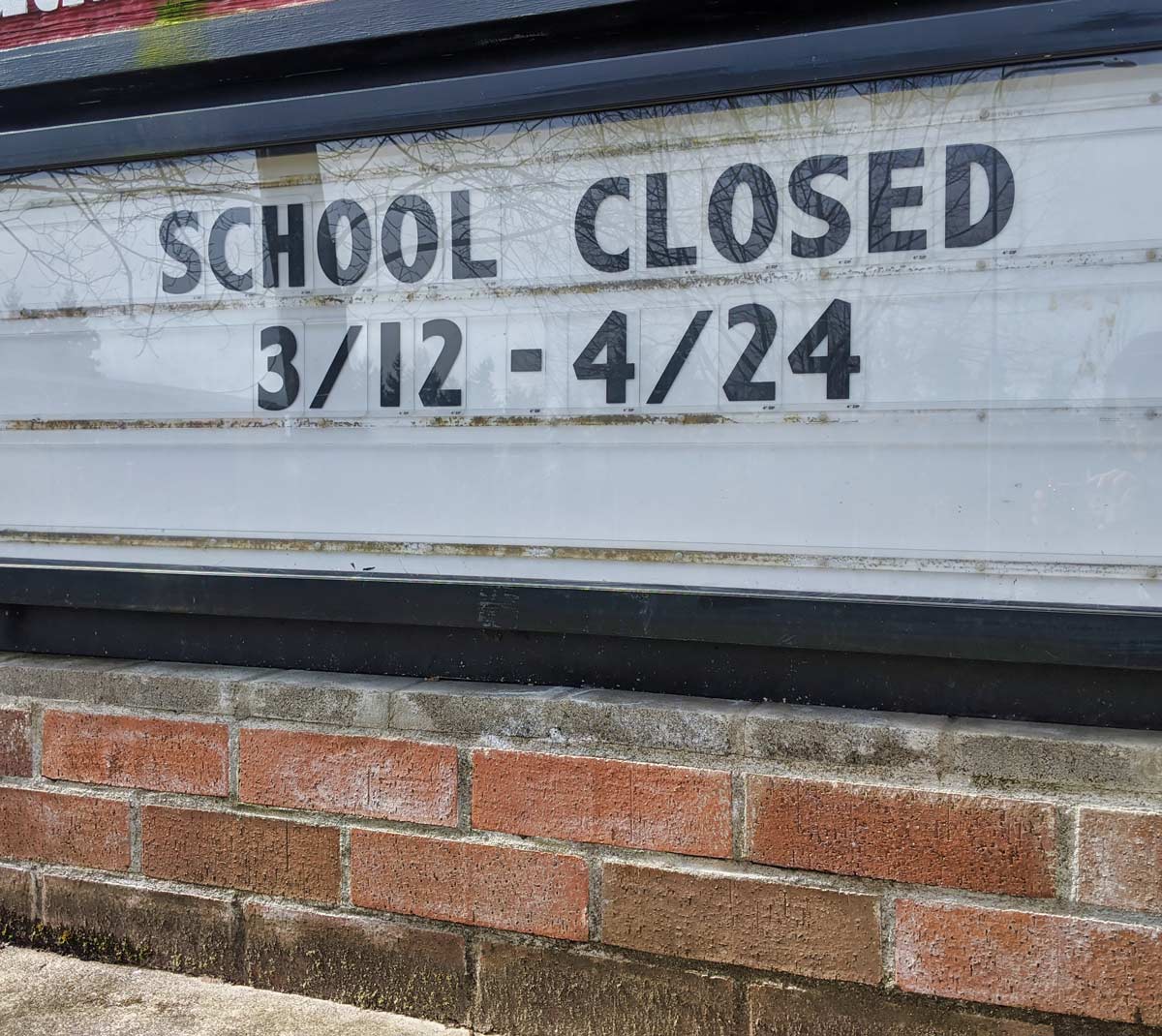

With nearly every California school closed due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, board members, administrators, teachers and classified employees are grappling with ways to continue educating and supporting the state’s 6.2 million K-12 students. During this difficult and unprecedented time, CSBA is working to serve its members by providing the most up-to-date information and guidance from both the state and federal government, as well as by collecting and sharing resources and examples of what districts are doing to address pressing issues such as distance learning, student well-being and meal distribution.

|

60.9% are low-income students |

16% had no internet connection at home in 2017 |

27% did not have broadband access in 2017 |

800,000 students receive special education services |

19.3% of students are English learners |

in the time of

coronavirus

|

60.9% are low-income students |

16% had no internet connection at home in 2017 |

27% did not have broadband access in 2017 |

800,000 students receive special education services |

19.3% of students are English learners |

are low-income students

had no internet connection at home in 2017

did not have broadband access in 2017

students receive special education services

of students are English learners

hile nearly every school in California is closed for physical instruction out of paramount health and safety concerns, they are still working tirelessly to address the basic needs of students and develop methods to engage them in quality distance learning,” CSBA CEO & Executive Director Vernon M. Billy said. “This is the most challenging time schools have ever faced, but together, we will continue to educate and care for the state’s 6.2 million students. CSBA is your association, and we are working to support board members with up-to-date resources and guidance. We are advocating for districts and county offices of education with legislators, the state superintendent of public instruction and the Governor, as well as working with public and private sector companies on your behalf to address digital inequities.”

hile nearly every school in California is closed for physical instruction out of paramount health and safety concerns, they are still working tirelessly to address the basic needs of students and develop methods to engage them in quality distance learning,” CSBA CEO & Executive Director Vernon M. Billy said. “This is the most challenging time schools have ever faced, but together, we will continue to educate and care for the state’s 6.2 million students. CSBA is your association, and we are working to support board members with up-to-date resources and guidance. We are advocating for districts and county offices of education with legislators, the state superintendent of public instruction and the Governor, as well as working with public and private sector companies on your behalf to address digital inequities.”  hile nearly every school in California is closed for physical instruction out of paramount health and safety concerns, they are still working tirelessly to address the basic needs of students and develop methods to engage them in quality distance learning,” CSBA CEO & Executive Director Vernon M. Billy said. “This is the most challenging time schools have ever faced, but together, we will continue to educate and care for the state’s 6.2 million students. CSBA is your association, and we are working to support board members with up-to-date resources and guidance. We are advocating for districts and county offices of education with legislators, the state superintendent of public instruction and the Governor, as well as working with public and private sector companies on your behalf to address digital inequities.”

hile nearly every school in California is closed for physical instruction out of paramount health and safety concerns, they are still working tirelessly to address the basic needs of students and develop methods to engage them in quality distance learning,” CSBA CEO & Executive Director Vernon M. Billy said. “This is the most challenging time schools have ever faced, but together, we will continue to educate and care for the state’s 6.2 million students. CSBA is your association, and we are working to support board members with up-to-date resources and guidance. We are advocating for districts and county offices of education with legislators, the state superintendent of public instruction and the Governor, as well as working with public and private sector companies on your behalf to address digital inequities.” With schools closed for in-person instruction and with computer labs, laptops and high-speed internet unavailable to students, districts are grappling with how to deliver quality digital lessons to all of their students. Districts have voiced a number of important concerns about this issue through CSBA’s COVID-19 membership surveys as they begin stepping up to the challenge by rolling out online learning plans and equipping students with technology through a variety of approaches.

Relationships with bargaining units

The immediate results provided many strong examples of collaboration between administrators and unions to move distance learning forward, mixed with notable instances of bargaining hold-ups that slowed such efforts. Many of the latter examples existed in districts with outstanding labor negotiations or disputes, with pre-closure bargaining relationships largely setting the tone for the transition to distance learning.

The dichotomy played out in Sacramento, where Natomas Unified School District and the Natomas Teachers’ Association quickly signed a memorandum of understanding outlining a calendar and staff expectations for distance learning. The weeks of March 30 and April 6 saw Natomas teachers pilot distance lesson plans with students as families were provided orientation and necessary resources.

Elsewhere in the county, negotiations between Sacramento City USD and its teachers association — an already strained relationship that saw a one-day strike in 2019 — continued into late March. In addition to negotiating details on working hours and teacher preparedness for distance learning, the Sacramento City Teachers Association highlighted the digital divide and equitable access for students as major concerns.

Beyond teachers unions, districts across California also turned to the bargaining table and MOUs to hammer out what the final few months of the school year would look like for classified and support staff, including bus drivers and custodians.

“We have a large geographical area with many of our students living 15 to 20 miles or further from our schools and some with no access to the internet,” said Lone Pine board member Krista Sullivan. Carmel USD board member Annette Yee Steck shared similar concerns, asking, “How can we get internet out to the very remote parts of our district so that students can access the work we have for them online?”

CSBA Director, Region 15, and longtime Los Alamitos USD board member Meg Cutuli said that in conjunction with the district checking out devices and WiFi hotspots to students who need them, district leaders put a premium on preparing educators for distance learning. “We needed to make sure that all teachers had computers to deliver the online learning, training on how to use the platform, support from the district (administrators and tech support) and time to also collaborate with their professional learning team,” she said.

Demand for technology and internet devices and services has also peaked worldwide during the pandemic, impeding plans for districts such as Elk Grove USD — the state’s fifth-largest district — which experienced a delayed arrival of 8,000 hotspots it ordered.

In unveiling its plan to launch school online with formal instruction and grading beginning on April 27, San Diego USD outlined several steps to prepare for the drastic departure from in-person classes. The state’s second-largest district is using the build-up time as a “soft launch” to train teachers for the move, work remotely with students who are able to participate and identify those students who are unable to take part. Officials also planned how to distribute about 40,000 district-owned laptops and mobile WiFi hotspots to students who need them.

“Students are missing out on valuable learning opportunities. The current situation is unsustainable and demands a solution,” Board President John Lee Evans said at the plan’s launch. “The solution we are announcing allows our students to continue their academic journey without the fear of spreading the COVID-19 pandemic.”

San Diego USD joined Los Angeles USD in a March 23 letter to state lawmakers calling for an emergency appropriation of at least $500 for every student in the state to cover the costs of online distance learning. Prior to submitting the letter, LAUSD inked a $100 million emergency contract with Verizon to provide internet connectivity for all students without it at home.

Such a sizeable contract, however, is not feasible for the vast majority of California’s school districts. CSBA will continue to press for investment in this critically important area through state and federal advocacy. A $2 billion allocation for broadband access for schools was in an earlier version of the federal stimulus package but was not included in the final $2 trillion bill passed on March 27.

Additional examples of district efforts to widen their reach of distance learning included Capistrano USD distributing laptops to parents during meal pick-up times, West Contra Costa USD briefly reopening schools to allow families to pick up Chromebooks and other materials, and Marysville Joint USD schools boosting WiFi signals so families could park outside and access internet-based learning tools.

When a school district continues to provide educational opportunities to the general student population during school closures, the district is also obligated to provide students with disabilities with equitable access to comparable opportunities, appropriately tailored to the student’s individualized needs, as determined through the IEP process. Depending on each student’s needs, their IEP and access to resources during school closures, complying with relevant federal laws may be particularly difficult during distance learning. LEAs must determine on an individual basis whether each student could benefit from online or virtual instruction, instructional telephone calls and other curriculum-based instructional activities, to the extent available, and follow appropriate health guidelines in the provision of such services.

—Kathryn Meola, General Counsel, CSBA

—Kathryn Meola, General Counsel, CSBA

California has nearly 800,000 students who receive special education services. The difficulty of complying with IDEA during school closures has led some districts away from providing distance learning in any capacity. Some districts — many of which were already in financial distress prior to the pandemic — are paralyzed by fear of litigation and see federal intervention as the only avenue forward. In a survey distributed by CSBA, almost every respondent pointed to special education as a significant challenge. “We need clarity on distance learning and special ed,” said one comment. “Everyone is afraid to do distance learning because we can’t meet IDEA requirements. There has to be a way to suspend IDEA requirements for education and then require some alternative for students with special needs. We can serve them. We WANT to serve them. But we need legal protection to do so.”

—Kristin Wright, director, CDE, special education division

—Kristin Wright, director, CDE, special education division

In surveying the practical landscape of distance learning, there will likely be delays in providing some special education services and in making decisions about how to provide such services. Guidance released on March 20 by the California Department of Education suggests that, in evaluating those delays, IEP teams will have to make determinations on a case-by-case basis about whether, and to what extent, compensatory services may be needed when schools resume normal operations.

The U.S. Department of Education fact sheet states that, “while some schools might choose to safely, and in accordance with state law, provide certain IEP services to some students in-person, it may be unfeasible or unsafe for some institutions, during current emergency school closures, to provide hands-on physical therapy, occupational therapy or tactile sign language educational services. Many disability-related modifications and services may be effectively provided online. These may include, for instance, extensions of time for assignments, videos with accurate captioning or embedded sign language interpreting, accessible reading materials, and many speech or language services through video conferencing.”

IDEA timelines may present challenges during this time, and the fact sheet includes additional information on IDEA timeframes that may need to be addressed, highlighting existing exceptions in the federal code and how the current crisis may fit within those provisions, including for initial evaluations, re-evaluations, complaint resolution, due process hearings and meeting and developing IEPs.

For example, if a child has been found eligible to receive services under IDEA, the IEP team must meet and develop an initial IEP within 30 days of a determination that the child needs special education and related services. However, parents and an IEP team may agree to conduct IEP meetings through alternate means, including videoconferencing or conference telephone calls. The Education Department encourages school teams and parents to work collaboratively to meet IEP timeline requirements. In making changes to a child’s IEP after the annual IEP team meeting because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the parent of a child with a disability and the public agency may agree to not convene an IEP team meeting for the purposes of making those changes, and instead develop a written document to amend or modify the child’s current IEP. The guidance encourages school districts and county offices of education to work with parents to reach mutually agreeable extensions of time, as appropriate.

In addition to its guidance issued on March 20, the CDE has formed a workgroup of special education practitioners and other experts to help brainstorm best practices that it plans to share in the coming weeks. The department also stated that it is committed to a reasonable approach to compliance monitoring that accounts for the exceptional circumstances facing the state.

In a March 18 webinar drawing roughly 7,000 viewers, Kristin Wright, director of the CDE’s special education division, offered a sobering assessment on how to move forward. “We’re not likely able to physically provide those supports and services that we’re all so used to, to the same degree that we have previously,” she said. “So, the first sentiment I want to reinforce is — do what you can.”

The CDE and the California State Board of Education are working with the federal Education Department to determine what flexibility or waivers may be issued in light of the extraordinary circumstances. Until and unless the U.S. Department of Education ultimately provides flexibilities under federal law, school districts and county offices of education should do their best in adhering to IDEA requirements, including federally mandated timelines, to the extent possible.

There are more than 1 million English learners throughout California, according to CDE data, comprising about 20 percent of the state’s student population. At the same time, nearly 42 percent of children speak a language other than English at home, a possible indicator that older members of their families may not be fluent in English.

It is vital during closures that officials consider the language barriers present in the community. This means that all communications from school districts during this time — whether it be handwashing tutorials, school closure announcements or updates on meal pick-up options — should be available in all languages spoken by students in the district.

School districts can also offer more personalized ways of connecting with English learner and immigrant families by working with community organizations and family liaisons who are likely to already have communication networks in place. Working with outside groups can be especially helpful when it comes to addressing meal pick-ups in districts with large populations of migrant workers or families working in service industries whose schedules do not allow them time to pick up food from school during the day. Offering off hours pick-up options or working with local restaurants that are still open for pick-up or delivery orders may be an option.

As districts shift to online learning, language barriers have become even more pronounced. The U.S. Department of Education found in 2019 that few teachers reported assigning English learners work that required digital learning resources outside of class, in part because of a lack of technology at home.

Due to widespread inequities in access to devices and internet, as well as a dearth of easily accessible translated digital curriculum, school officials must make available an array of approaches to ensure access to online learning opportunities. Recommendations from Colorín Colorado — a comprehensive resource for educators and families of ELs — include taking school supplies to migrant farmworkers who live in trailer communities; sharing activity ideas with families; and for those with no internet access, providing tech-free coursework.

While many districts in California are equipped to provide healthy meals and mental health care during the school day, the sudden and extended school closures have left education officials with more questions than answers as they scramble to be creative in providing for students in need.

Districts are assessing local needs and circumstances and developing different approaches to accommodate their communities. Stockton USD is reaching out to students who were receiving school-based mental health services prior to school closures to arrange telehealth services. The district also established a helpline that students and families can use to speak directly to mental health clinicians, child welfare and attendance staff and other health personnel during school closures. Mental health and behavior staff were also made available to answer questions and provide guidance for accessing community resources.

Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue on March 26 announced additional flexibilities to make it easier for schools to provide food for families during the COVID-19 emergency by removing administrative red tape. Prior to the announcement, children had to be present at pick-up to receive a school meal through USDA’s child nutrition programs. Under the new waiver, states can allow parents or guardians to take meals home to their children. This change can be especially helpful for families with children who are sick, have a disability that makes transporting them difficult, or for parents who need to plan meal pick-ups around work schedules. Other waivers allow for after-school meals and snacks to be served without the requirement that doing so be accompanied by educational activities, suspends mealtime requirements and allows for non-congregate meal consumption.

Yet, even with certain meal provisions waived, districts are finding it difficult to provide school meals in ways that meet social distancing guidelines or the needs of their families — especially in high-need areas — as indicated through CSBA’s member survey. One respondent representing a district where 81 percent of children qualify for free and reduced-price meals expressed concern for those families that could not make it to schools for food pick-ups. “Our district serves a community that is 83 to 85 percent below poverty. We are in a nutrition desert, and our district is delivering meals to our students because lack of transportation overlaps as a barrier for our families.”

To best accommodate the largest number of families in need, 24 school districts and six charter schools in Monterey County are providing free meals for all children during the COVID-19 school closures. In Los Angeles USD staff members hand bags of food to drivers as they pull up to “grab-and-go” meal sites operating throughout the district. The small Robla School District in Sacramento is taking meals to designated stops throughout the district as part of its Breakfast on Wheels and Lunch on Wheels programs. Twice a week, district buses stop throughout neighborhoods and provide multiple days’ worth of breakfasts and lunches for all children under the age of 18.

The CDE has made guidance available (bit.ly/2wBSFkA) that provides suggestions for meal distribution methods that allow for social distancing, such as serving out of a food truck or sending a box or bag of meals home with students for multiple days.

In this fast-moving situation, CSBA is working to provide its members with the most up-to-date information and guidance through www.csba.org/coronavirus and email updates to your inbox. “We look forward to a time when we can gather together again,” said CSBA President Xilonin Cruz-Gonzalez. “In the meantime, we are creating new systems for learning and addressing inequalities that will contribute to a more equitable school environment in the future.”