Threat

Threat

Assessment

Protocol

An Important Step to Prevent School Violence

BY HUGH BIGGAR

Threat

Threat

Assessment

Protocol

An Important Step to Prevent School Violence

BY HUGH BIGGAR

a spring afternoon this year, school safety expert Amy Klinger sorted through online news stories and social media posts using such search terms as ‘gun threats’ and ‘bomb threats.’ On Instagram, she came across one gun violence threat against a school that had been shared more than 120,000 times.

For Klinger and other school safety professionals, that threat was just one of the many that spiked in the days and months following a deadly mass shooting at a Parkland, Fla. high school in February 2018. School leaders who are now facing an increase in such threats are grappling with how to best assess them and trying to stay ahead of a potentially serious incident.

Klinger’s organization, the Ohio-based Educator’s School Safety Network, is one of only a few that are tracking information related to threats of campus violence. As of May, the Educator’s School Safety Network found that, in the first four months of 2018, there were roughly 1,500 threats of violence impacting more than 1,800 schools across the United States.

“After Parkland, the perfect storm arrived for threats, including media attention, social media and copycat threats,” Klinger said by phone, as she drove to Columbus to speak to the state legislature about the issue. “It made for a contagious environment and one educators can’t just ignore.”

To help school officials assess these threats, experts have established guidelines and checklists with the uniform caveat that there is no one identifying factor.

“There is no predictor tool, as there is no consistent profile that can confidently predict human behavior,” said Melissa Reeves, an associate professor of psychology at Winthrop University in South Carolina and a former school psychologist. “However, there are patterns of behavior coupled with risk factors, warning signs and significant stressors which help determine if an individual may be on a pathway to violence.”

“After Parkland, the perfect storm arrived for threats, including media attention, social media and copycats threats. It made for a contagious environment and one educators can’t just ignore.”

—Amy Klinger, school safety expert

“After Parkland, the perfect storm arrived for threats, including media attention, social media and copycats threats. It made for a contagious environment and one educators can’t just ignore.”

—Amy Klinger, school safety expert

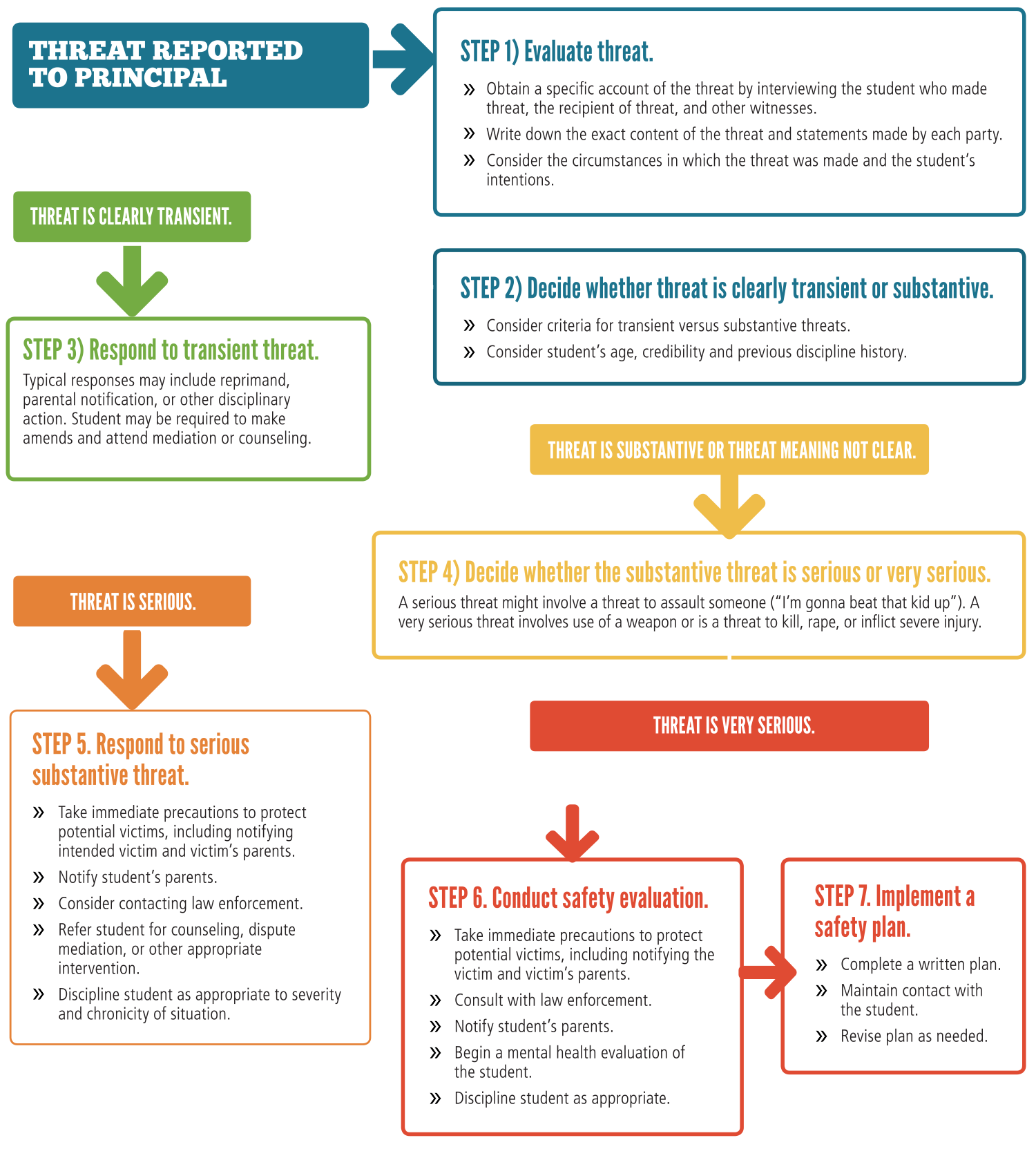

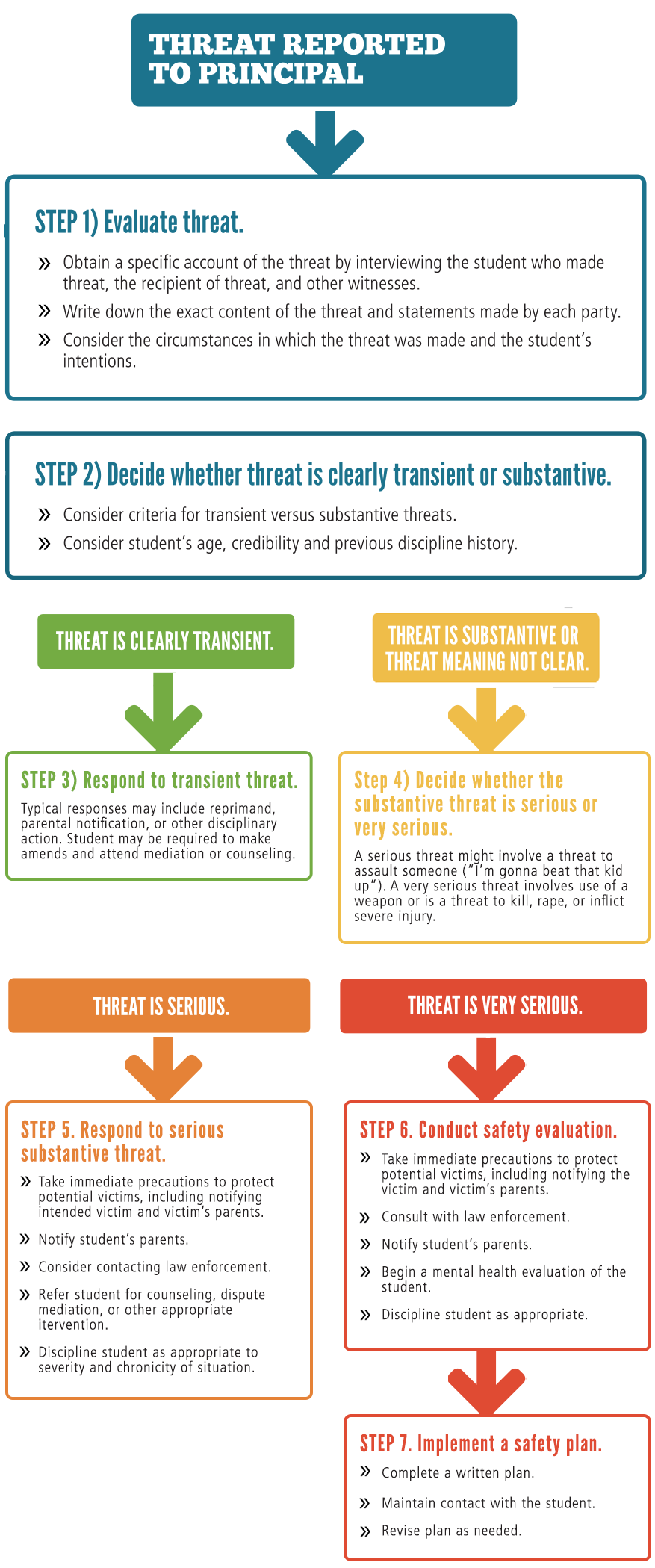

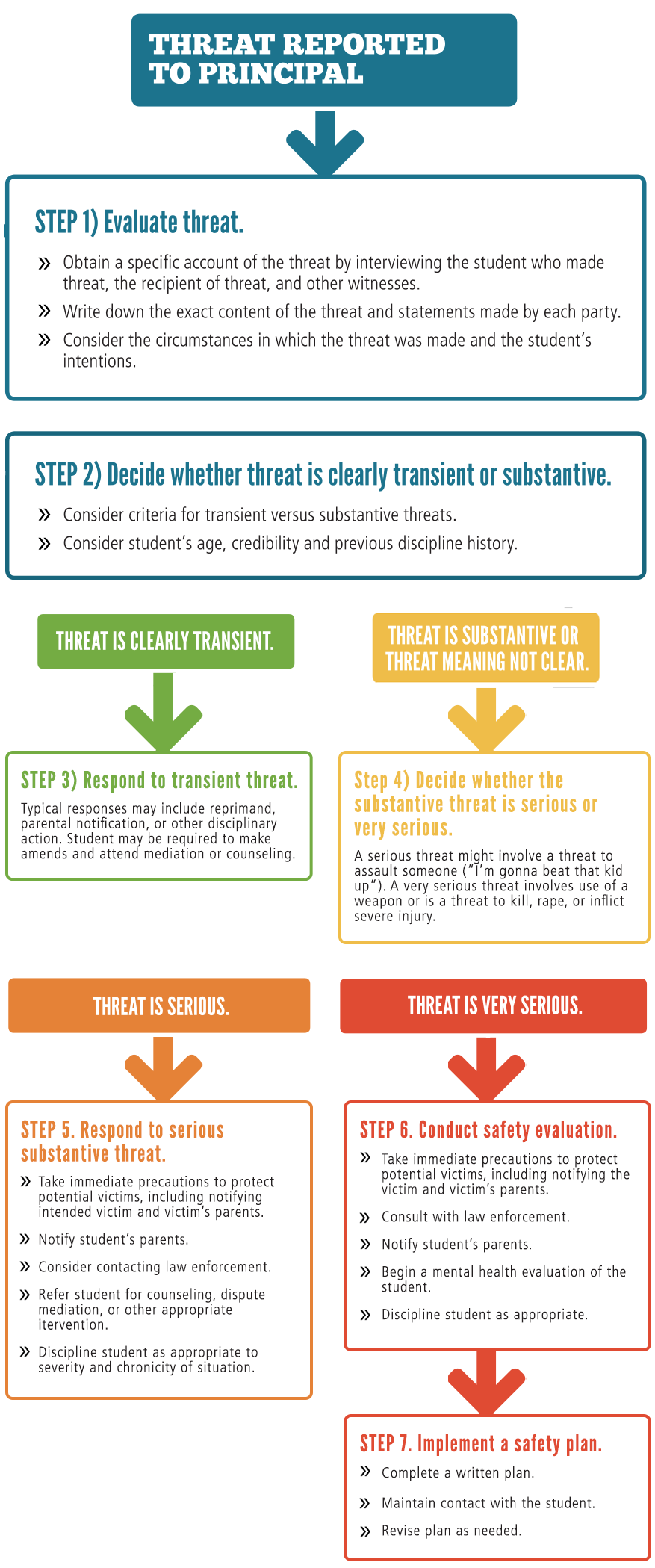

As part of efforts to prevent a violent incident from happening in schools, school leaders have drawn from academic research to develop tools and practices to better assess threats against schools. One of the most common approaches is known as behavioral threat assessment and management, or BTAM. BTAM involves the use of a multi-disciplinary team of school personnel to mitigate behavioral threats on campus through an integrated process of communication, education, prevention, problem identification, assessment, intervention and response to incidents. The group should include a district administrator, a building administrator, at least one teacher or member of the staff, school mental health staff and, if available, a school resource officer. If a student presents as a threat, makes a threat or indicates potential violence, the team begins the process and consultations. Warning signs can include verbal threats, anti-social behavior, hostile emotions and aggression toward others. Another useful tool is a seven-step process to evaluate school threats developed by researchers at the University of Virginia. The steps move from evaluation to response to safety planning.

These Lammersville USD safety procedures align with the recommended practice for local educational agencies to have a coordinated response, be cautious and informed, and to not overreact. As part of this approach, experts say not all school threats should be treated the same, and information gathered on individual students and school climate play an important role in determining the validity of the threat.

Warning signs can include verbal threats, anti-social behavior, hostile emotions and aggression toward others.

Warning signs can include verbal threats, anti-social behavior, hostile emotions and aggression toward others.

The Educator’s School Safety Network’s Klinger echoed this proactive strategy, saying it is critical to stay on top of early warning signs of a troubled student. Reeves, co-author of the first national school crisis intervention and prevention curriculum, agreed. According to Reeves, “It is important to have a school threat assessment team in place if at all possible.”

In California however, staffing cuts in schools during the last recession reduced critical components of assessment teams. School counselors, for instance, have some of the highest student caseloads nationally. There are also severe shortages of nurses at schools statewide.

Given this reality, Reeves said community partnerships can help bridge gaps in training and mental health services and interventions for students.

Student Threat

Assessment

Source: The Virginia Model for Student Threat Assessment, Dewey G. Cornell, Ph.D., University of Virginia, 7-16-10

Student Threat

Assessment

Source: The Virginia Model for Student Threat Assessment, Dewey G. Cornell, Ph.D., University of Virginia, 7-16-10

Student Threat

Assessment

Source: The Virginia Model for Student Threat Assessment, Dewey G. Cornell, Ph.D., University of Virginia, 7-16-10

“Our struggle in schools is we can identify students in need of help and know what they need, but there are often not enough resources in schools and in communities to meet some of the emotional and behavioral challenges we see,” she said.

Some California school districts have already turned to local resources for support.

The Mariposa County Unified School District near Yosemite National Park, for example, partnered with Mountain Crisis Services to implement an anti-bullying program, one that has since grown to include an initiative to address teen dating violence. The initiative includes peer support groups for students, relationships skills classes, training school staff to recognize warning signs and working with parents and other community groups.

In Southern California, the Murrieta Valley Unified School District established a safe schools program in response to a rise in gang activity. Since its launch, the program has stressed three criteria: communication, school and law enforcement partnerships and staff trainings. The district has also involved students by creating student focus groups and student-led forums to help create a culture of respect, trust and positive behavior to help prevent aggressive behavior.

“One act of school violence is too many,” said Reeves.

Hugh Biggar is a staff writer for California Schools..

Resources

CSBA sample policy: BP/AR 0450 — Comprehensive Safety Plan

California Department of Education Threat Assessment: cde.ca.gov/ls/ss/vp/safeschlplanning.asp

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Understand School Violence: https://bit.ly/QvQSmy

Educator’s School Safety Network: eschoolsafety.org/

National Association of School Psychologists: https://bit.ly/2ymzL1n

School Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management: https://bit.ly/2lkNyfo

The University of Virginia Model for Threat Assessment: curry.virginia.edu/virginia-model-student-threat-assessment

CSBA sample policy: BP/AR 0450 — Comprehensive Safety Plan

California Department of Education Threat Assessment: pubs.cde.ca.gov/tcsii/ch8/threatassess.aspx

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Understand School Violence: https://bit.ly/QvQSmy

Educator’s School Safety Network: eschoolsafety.org/

National Association of School Psychologists: https://bit.ly/2ymzL1n

School Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management: https://bit.ly/2lkNyfo

The University of Virginia Model for Threat Assessment: curry.virginia.edu/virginia-model-student-threat-assessment