Bust

Enrollment

Adds New

Challenges

for California

Schools

Bust

Enrollment

Adds New

Challenges

for California

Schools

n recent years, California’s birth rates have flatlined as families are increasingly delaying having children or moving out of the state in search of lower costs of living and affordable housing. These population changes are now hitting cash-strapped California school districts already facing rising costs, increased pension obligations and chronically low state funding. How to balance these entangled demographic and financial pressures without sacrificing educational services and quality is a pressing issue for many districts, one that LAUSD and others are hoping to transform from a potential crisis into an opportunity.

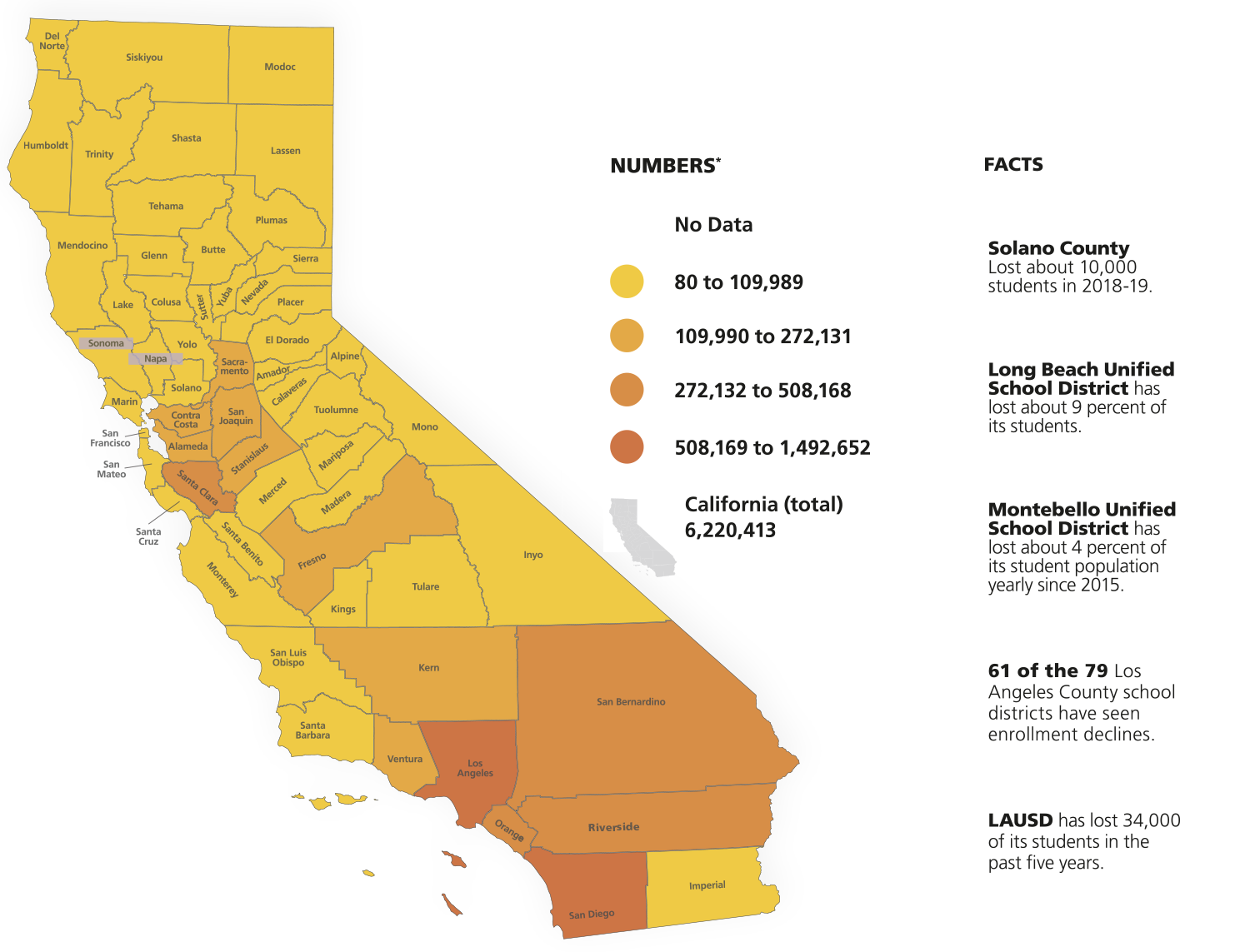

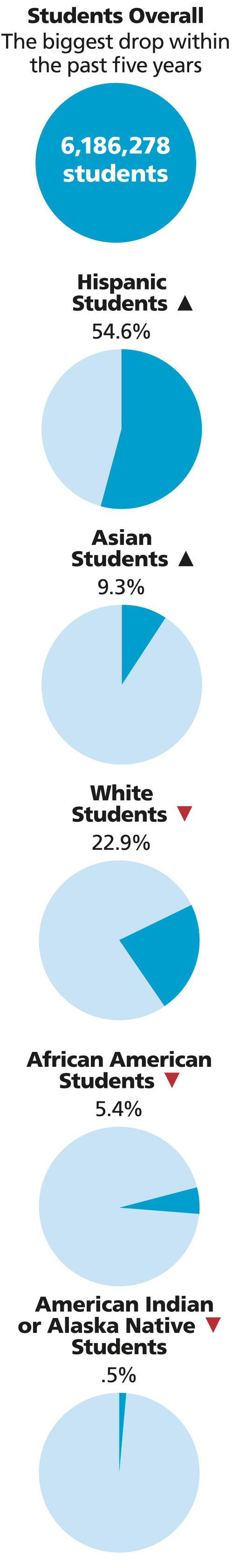

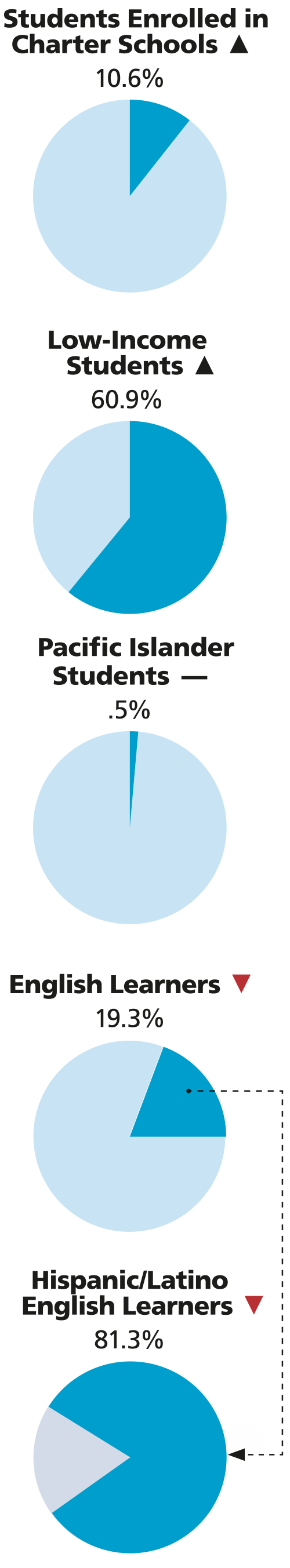

According to the latest statistics from the California Department of Education, 34,135 fewer students enrolled in the state’s K-12 public schools in 2018–19 compared to the year before. In the past five years, enrollment has dropped by 0.8 percent, from 6,235,520 in 2014–15 to 6,186,278 in 2018–19. As a result, about half of the state’s nearly 1,000 districts have experienced enrollment losses.

Other areas, including those with lower costs of living, have also seen falling enrollment. Solano County, north of San Francisco, has lost about 10,000 students in the past 20 years. Near Palm Springs, a drop in school enrollment, combined with increased special education needs and contributions to teacher pensions, is stretching districts financially. In the Santa Clarita Valley, districts have seen increases in class sizes and reductions in staff as enrollment has decreased. In San Diego County, charter schools have grown but non-charter school enrollment has dropped by 13,301 students since 2014–15. The Montebello Unified School District in L.A. County has lost about 4 percent of its student population each year since 2015, or 880 students annually.

While these numbers could fluctuate, and some areas of California, such as Riverside and Kern counties, have seen school growth, the overall trend of falling enrollments adds a new fiscal burden for already financially challenged districts.

After Prop. 13’s passage — which capped residential and commercial tax assessments at 1970s levels for many property owners — California moved to funding tied to average daily attendance, Warren explained. This made many schools reliant on strong enrollment numbers to sustain educational programs and staff hiring. At the same time, state support for schools also dropped. After ranking at the top for state education funding in the early 1970s, California is now among the bottom 10 nationally for the amount it spends per student. Similarly, average class sizes have grown to among the largest nationally and the number of nurses, librarians and guidance counselors in schools has plummeted. Today, California is the 45th-ranked state for the tax revenue it spends on schools, despite boasting the fifth largest economy in the world.

Declining enrollment can add to these downward trends and seriously affect teaching and learning.

“It places strain on the budget of a district,” said Manuel Buenrostro, CSBA education policy analyst. “Districts often have to make decisions about cutting programs, teaching positions and other support staff. Moreover, adjusting the budget can be difficult when we consider the fixed costs that districts have, such as pension and health care payments for retired staff, maintenance of facilities and others.”

Under California’s funding system, schools are guaranteed an average daily attendance amount per pupil under the Local Control Funding Formula. Supplemental and concentration grants can then boost funding for districts with large numbers of foster children, English learners or low-income students. But these amounts are also tied to daily attendance and higher-poverty districts are less able to generate local revenue without state help, creating a slippery slope for funding.

“Schools are already hurting,” the PPIC’s Warren said, “and the financial pressures from enrollment decline are going to limit their flexibility to provide programs and keep teachers.”

Enrollment in 2018–19

That reality has included an 18 percent drop in enrollment in the past 15 years, combined with a 19 percent drop in the school-age population of 5- to 17-year-olds. Along the way, the district has experienced the financial strains of the Great Recession, the rise of charter schools that can siphon off students and revenue from neighborhood schools, and most recently, teacher strikes concerning pay, learning conditions and resources.

In one example of the toll enrollment loss has taken, LAUSD has gone from having a librarian in every school, to using library aides, to closing some elementary school libraries or operating them only on certain days.

“The more enrollment declines, the higher percentage of a district’s funding per student will go to fixed costs, leaving less for the classrooms,” CSBA’s Buenrostro said.

Similarly, the LAUSD report wrote, “Although fewer students require fewer teachers and schools, revenues can fall more quickly than the fixed costs of personnel and facilities, placing pressure on budgets and requiring strategic responses.”

“Declining enrollment may also affect the concentration of need in our schools,” said Kelly Gonez, an LAUSD school board member and CSBA Director for Region 21. “If more students are opting out of traditional district schools, whether for private schools, charters or other school districts, we find greater proportions of students with high needs in our schools. And these students naturally require more resources to educate. Additionally, fewer students on campus causes teacher displacement, which creates a lack of stability at schools, disrupts instruction and decreases staff morale.”

While LAUSD expects its student population to eventually stabilize but not entirely recover to previous highs, its consultants in the interim have recommended both short-term and long-term strategies to retain students. At the top of the list is offering high-quality schools to attract students and families and offering niche programs centered on the district’s strengths. Those programs could include early childhood education and dual-language instruction.

Near Los Angeles, the Downey Unified School District is trying a similar approach to offset losing 300 to 400 students a year.

“The district is starting a dual-immersion Spanish school and investigating expansion to a school with an International Baccalaureate program for 2021,” said Donald LaPlante, Downey USD trustee and Region 24 CSBA Director. “The district is also aggressively marketing our programs to students who may have gone to other districts for child care or special programs along with students in private schools.”

In Montebello USD, school board President Edgar Cisneros said the district is taking several steps to highlight school attributes. These efforts include acquiring new textbooks and creating a popular districtwide showcase that recognizes academic achievement and attendance, as well as promoting educational initiatives.

“This is important because these programs, such as pathways and our Dual Immersion Academies, demonstrate an increase in interest and enrollment,” Cisneros said. “Our Dual Enrollment program is a partnership with our local community college which allows our students to take free college courses on our campuses.”

San Diego County Board of Education trustee Rick Shea noted that California districts are protected from the immediate impact of reduced enrollment by having a buffer year before funding goes down. “Once a decline is identified, a plan should be developed and enacted sooner rather than later,” he advised. “Assume decline will continue, so create multi-year and multi-tier plans.”

Meanwhile, in LAUSD, Gonez said the district is investing in STEAM magnets, dual-language programs, and even single-gender public schools. ”Most important for me, though, is to focus on strengthening all our schools,” she said, adding the district is about to roll out a new way for families to evaluate schools. “By continuously improving all our schools, we ensure our schools are attractive to families and that our families want to stay with their neighborhood school.”

At the state level, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s education agenda includes promising initiatives to provide schools and districts with more money and pension relief. There is also the possibility that the commercial component to Prop. 13 could be rolled back under a 2020 ballot measure. Other policy changes, such as increasing the amount of affordable housing in high-cost areas, could help districts attract families with children as well.

In the meantime, the PPIC’s Warren likens the impact of declining enrollments on schools and budgets to a rapidly diminishing pie.

“Instead of having extra pie for all, it works in reverse,” he said, “with more and more pieces taken out and less available for everyone else.”

Hugh Biggar is a staff writer for California Schools.