enrollment is affecting

California education

here is no doubt the pandemic profoundly disrupted schooling nationwide. Despite the best efforts of governance teams, teachers, parents and policymakers, experts have raised serious concerns about the impact of remote instruction on children’s learning, existing inequities, students’ mental and social-emotional health and more — and that’s among students who were enrolled in school during the 2020–21 and 2021–22 academic years.

Faced with the prospect of online kindergarten, many families opted to forego it altogether or, for those with the means and ability, find an in-person alternative to their local public school’s offerings.

Achievement gaps have long existed along racial and economic lines. On average, children living in poverty start school as much as a year and a half behind in their developmental levels than children who are from more affluent families, explained Deborah Stipek, the Judy Koch Professor of Education at Stanford Graduate School of Education and an expert in early childhood. COVID has simply exacerbated that.

Research released in March by Policy Analysis for California Education shows lost learning due to school closures has already impacted the ability of students in early grades to read aloud quickly and accurately. The study found yearly gains in oral reading fluency were 26 percent lower than expected based on prior years for second-graders in more than 100 school districts across 22 states, and 33 percent lower among third-graders.

“I suspect that unless we implement some things like tutoring, small classrooms, extra teachers and additional support for kids, what’s going to happen is students are going to start with a bigger gap, and that bigger gap is going to be maintained throughout school,” said Stipek.

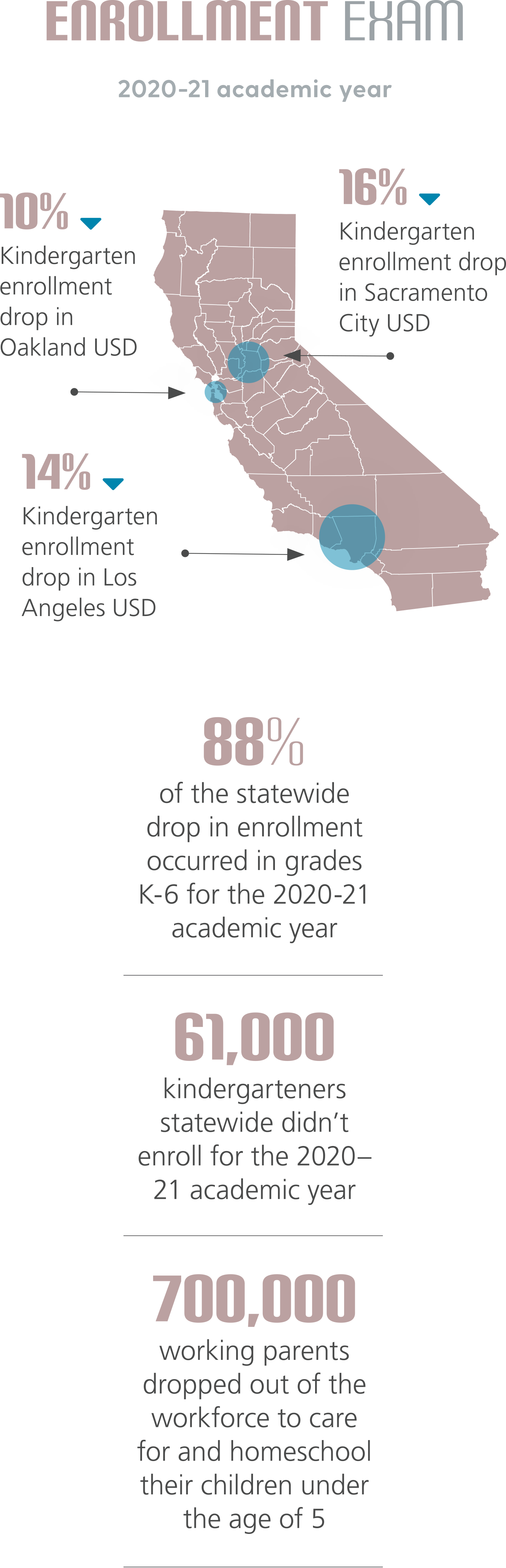

The California Department of Education released official enrollment data for the 2020–21 academic year on April 22. The annual snapshot spotlighted a sharp one-year decline in enrollment overall, but one that was particularly drastic among early grades. Eighty-eight percent of the statewide drop in enrollment occurred in grades K-6, with 61,000 missing kindergarteners alone accounting for more than a third of the total enrollment decline.

According to Sacramento City Unified School District data, kindergarten enrollment was down almost 16 percent; Los Angeles USD staff said enrollment declined 14 percent from the prior school year; and Oakland USD officials said the district saw a decline of roughly 10 percent.

It’s unlikely that many families chose to forego education all together this past year, said Gennie Gorback, president of the California Kindergarten Association and former early childhood educator based in Orinda.

“Many families had to get creative with schooling and had to determine the best course for their own family,” Gorback said. News reports confirm that families who could afford other options such as private schools or hiring individual tutors or organizing small learning pods often opted to do so.

Additionally, recent data analysis by the Center for American Progress found that about 700,000 working parents with children under the age of 5 — especially mothers — dropped out of the workforce to care for and homeschool their children.

Los Angeles USD Trustee Nick Melvoin noted that part of the challenge is that children would have had to enroll in the spring, at the height of all the uncertainty surrounding the virus.

“There were parents who’ve mentioned they didn’t want their children to be on screens all day, and it’s not lost on me that on March 12 of 2020, we were telling parents ‘too much screen time is bad, don’t be on screens,’ and then on March 13, we’re like, ‘screens all day!’” he said. “And I think the uncertainty and safety concerns were there too. Parents weren’t sure what it was going to look like. There were a lot of parents who didn’t want their kids’ first experience with school to be on Zoom. They’d rather just wait because they could.”

Such outcomes are less surprising when one discovers all that children learn in a kindergarten classroom that sets them up for success as they graduate from one grade and life stage to the next.

“Kindergarten is a child’s bridge into elementary school,” said Gorback. “Before learning phonics, a child must have phonological awareness skills. That means they have to be able to identify and manipulate the sounds in words. In order to prepare a child’s brain for reading, teachers plan intentional games and lead specific songs to target the phonological needs of their students.”

In addition to gaining the necessary building blocks to learn how to read and complete math problems, kindergarten also offers opportunities for children to develop the fine motor skills, impulse-control, self-regulation and communication skills necessary to problem-solve, play well with others and follow directions. Much of this is accomplished through play, songs and academic games and activities tailored to accommodate the ways in which young children learn.

“Kindergarten has changed quite dramatically, just even in the last 10 or 15 years,” Stipek said. “We’ve learned in research and in practice that young children are capable of learning a lot more than we thought they were.”

Garcia recounted a recent conversation with her daughters, now in sixth grade, about the lessons from their early learning speech and debate enrichment program and how it prepared them to not only speak in public, but also to develop and articulate an argument — a skill critical in writing college papers.

“They both remembered that in kindergarten they learned how to write a paragraph like a hamburger: the top bun is their topic sentence, the bottom bun is their conclusion, and everything in between — the patty, lettuce, tomato, pickle, etc. — is your argument and evidence, and the more evidence you have, the better,” she said. “This is what our kids are learning in kindergarten today.”

Sen. Susan Rubio (D-Baldwin Park) took a sixth swing at making kindergarten mandatory with Senate Bill 70, which would have required all students in California to complete one year of kindergarten before entering the first grade, beginning with the 2022–23 school year. The bill was held in the Senate.

Melvoin, whose district LAUSD sponsored the bill, said that while the majority of the district’s first-graders attend its full-day kindergarten program, requiring it would help with school readiness by getting the rest of those kids in available slots.

“I’d ultimately like to then see preschool become mandatory,” Melvoin said. “Right now, if we saw a district that didn’t start until second grade, we’d say ‘that’s crazy, how can you start school at age 7?’ I want in a generation for people to look at districts and ask, ‘how could you have only started school at 5?’”

Those who challenged the bill cited parental choice and concern over the perceived lack of play in some kindergarten classrooms, but more often, those opposed to SB 70 and past iterations of the bill pointed to the absence of attached funding for the increased enrollment — particularly now, at a time when local educational agencies are already struggling to balance budgets amidst a pandemic.

Under current law, the state provides average daily attendance funding at the same amount for both full-day and half-day kindergarten programs. Opponents argue this means implementing full-day kindergarten will be an extra expense for those districts that do not yet offer it or that will need to add classes to accommodate an influx of children. Further, districts will not have state matching dollars to retrofit or construct new classrooms to support additional growth or to hire additional teachers.

Garcia, who supports mandatory kindergarten, said the focus should be on helping districts provide full-day kindergarten in particular. In addition to aligning more closely to the adult workday, full-day programs are important for all young learners — especially those who didn’t have a chance to attend preschool or come from higher-needs communities, she said.

“We definitely need the state to commit [to funding],” said Melvoin. In the meantime, LAUSD is examining steps to boost kindergarten enrollment through community outreach to the local patchwork of early learning and childcare providers already working with community organizations.

The district has also been working on a unified enrollment system so parents can go to one website and see all their options, he said, noting that he wants to see a kindergarten pathway at every school.

District staff in Sacramento City USD is, as of this writing, working on expanded learning opportunities to mitigate learning loss among all students, including early learners going right into first grade in 2021–22 with drastically different levels of readiness. The initial summer program will focus on academic and social-emotional interventions and enrichment programming, Garcia said. Expanded learning opportunities will be available throughout the 2022–23 school year as well.

“I saw some kindergarten teachers who are doing some amazing things on the computer. I mean, amazing things, engaging their kids. But a lot of kids just couldn’t do it, or it required so much parent input and not all parents were able to sit next to their child and do school with them,” she said. “The degree to which kids could actually benefit from kindergarten online vary depending a lot on a family’s resources and abilities to offer ongoing support to the child. And it varied depending on the skills and creativity of the teacher. It’s not just their own personal creativity, but the support that they had.”

First-grade teachers in particular should be prepared to start the year understanding that many children will likely need help building the critical skills in reading and math that they didn’t master in kindergarten, as well as the basics learned through socialization, like raising hands to get called on or to form a line.

“I believe all teachers will have to go back to revisit and refresh basic material from the previous grade at the beginning of the year before moving forward,” Garcia said. “For first-grade teachers, it could mean a classroom of young learners with varying degrees of preparation, from academics to social interactions.”

With proper support, Gorback said she has no concern that first-grade teachers will be able to assess readiness to adjust to student’s needs and get kids excited about school. Districts can help, she said, by offering summer ‘jump start to kindergarten’ programs to help kids get used to attending school before school officially starts.

Melvoin said to support educators in the coming year — particularly those who teach early grades where students will be acclimating to a classroom in person for the first time — LAUSD is considering interventions including adding days to the school calendar, class size reduction, hiring more teachers’ aides and helping educators better assess academic readiness.

In addition to those types of proven interventions, tutoring can especially beneficial, as can continuing to engage parents in productive ways, Stipek said.

“A lot of parents would like to be able to help their children learn, but they don’t know exactly what they should be doing,” she explained. “One of the things teachers can do is provide them with some guidance so that the parents can extend what’s going on in school — all that takes time and training. My hope is that as teachers have gotten more used to communicating with parents about the children’s needs and ways that they can support children, that that will continue even when parents aren’t playing the active role that they’ve had to play this year.”

Ultimately, supporting students as they enter the classroom, families as they heal from a traumatic year, and teachers as they continue supporting children and themselves will all be equally important.

Gorback said she hopes that all the difficulties communities have faced and overcome will lead to a renewed focus in the Legislature on minimizing class sizes and increasing mental health and other support systems for everyone in the education community.

There is no doubt the pandemic profoundly disrupted schooling nationwide, just as there is no doubt among school boards that there has never been a more important time to step up to the challenge of supporting youth.

“It’s too soon to assess the true impact that COVID-19 has had on our students, teachers and school site staff. I think it’ll be several years before we fully see the arc of the loss — both academic and social-emotional,” Garcia said. “I recognize that most of us have never seen anything like this before, nor have had to deal with anything at this scale and with such high stakes. As educational leaders in our communities, we have a responsibility to do everything we can do to provide the necessary supports to mitigate the impact. I just can’t give up.”

Alisha Kirby is a staff writer for California Schools.