“What nobler employment, or more valuable to the state than that of the man who instructs the rising generation?”

— Marcus Tullius Cicero

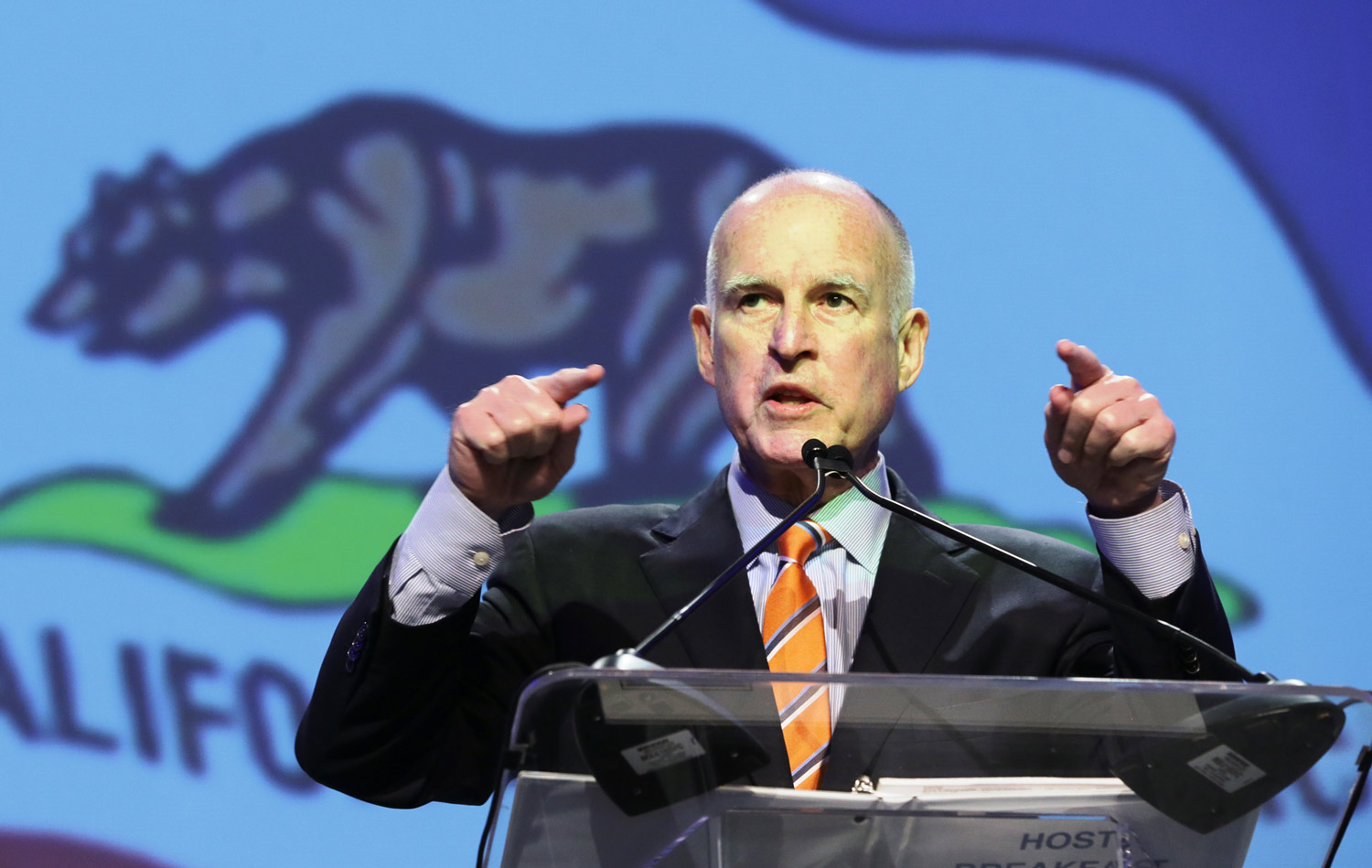

Grading Jerry Brown on education

by Troy Flint

Edmund Gerald Brown Jr. is California’s 34th and 39th Governor, a scion of the state’s most famous political family, a former seminarian and a classics scholar known to pepper his oratory with Latin. It’s probably no coincidence that the Roman philosopher and politician Marcus Tullius Cicero ranks among his favorite thinkers.

In one of Cicero’s more famous works, De re publica, he argues that the ideal citizen is the philosopher-statesman, as he is most capable of managing a city’s affairs well.

Cicero’s writing heavily influenced the founding fathers, as well as Brown, who compared his speeches to a symphony and considered them “the clearest you would ever want to read.”1

Brown’s appreciation for the ancient world deepened during his time at Sacred Heart Seminary, but dates back to his days at San Francisco’s St. Ignatius High. At St. Ignatius, pupils studied Latin five days a week and honor students took Greek — the only other language offered.

Although St. Ignatius was an elite school, it also prided itself on an egalitarian streak. In the words of Brown family biographer, Miriam Pawel, “St. Ignatius drew students from all over the city, its reputation based on achievement rather than the social stature of parents. Working-class kids mingled with children of the elite, embodying the California idea of education as the great equalizer and avenue to upward mobility.” Education as an engine for equality and prosperity (and political necessity) is central not only to California’s self-image, but also to the Brown family history.

“There’s a wonderful story I heard Kathleen [Brown] tell in her father’s presence and that Jerry told at his father’s funeral,” recalled former California State Assemblymember and Superintendent of Public Instruction Delaine Eastin. The story concerns an exchange between Pat Brown, who served as California’s 32nd Governor and — until Jerry — its longest-serving chief executive, and his wife, Bernice.

“It’s the day after he was elected Governor and Pat is in the car. He turns to Bernice and said, ‘We lost Orange County, we lost San Diego County, and we lost Santa Cruz County — what are we going to do to win them next time?’ Bernice said, ‘You’re going to have to educate them. So, Pat built UCSD, UC Irvine, and UC Santa Cruz — one Governor built one-third of UC.’”

That calculation, combined with the desire to increase social mobility and provide greater college access for a burgeoning population, resulted in The California Master Plan. Adopted in 1960, the Master Plan essentially made California the first state to, in theory at least, guarantee universal access to higher education. Along with the California State Water Project, the Master Plan became the most enduring part of Pat Brown’s legacy.

Grading Jerry Brown on education

by Troy Flint

Edmund Gerald Brown Jr. is California’s 34th and 39th Governor, a scion of the state’s most famous political family, a former seminarian and a classics scholar known to pepper his oratory with Latin. It’s probably no coincidence that the Roman philosopher and politician Marcus Tullius Cicero ranks among his favorite thinkers.

In one of Cicero’s more famous works, De re publica, he argues that the ideal citizen is the philosopher-statesman, as he is most capable of managing a city’s affairs well.

Cicero’s writing heavily influenced the founding fathers, as well as Brown, who compared his speeches to a symphony and considered them “the clearest you would ever want to read.”1

Brown’s appreciation for the ancient world deepened during his time at Sacred Heart Seminary, but dates back to his days at San Francisco’s St. Ignatius High. At St. Ignatius, pupils studied Latin five days a week and honor students took Greek — the only other language offered.

Although St. Ignatius was an elite school, it also prided itself on an egalitarian streak. In the words of Brown family biographer, Miriam Pawel, “St. Ignatius drew students from all over the city, its reputation based on achievement rather than the social stature of parents. Working-class kids mingled with children of the elite, embodying the California idea of education as the great equalizer and avenue to upward mobility.” Education as an engine for equality and prosperity (and political necessity) is central not only to California’s self-image, but also to the Brown family history.

“There’s a wonderful story I heard Kathleen [Brown] tell in her father’s presence and that Jerry told at his father’s funeral,” recalled former California State Assemblymember and Superintendent of Public Instruction Delaine Eastin. The story concerns an exchange between Pat Brown, who served as California’s 32nd Governor and — until Jerry — its longest-serving chief executive, and his wife, Bernice.

“It’s the day after he was elected Governor and Pat is in the car. He turns to Bernice and said, ‘We lost Orange County, we lost San Diego County, and we lost Santa Cruz County — what are we going to do to win them next time?’ Bernice said, ‘You’re going to have to educate them. So, Pat built UCSD, UC Irvine, and UC Santa Cruz — one Governor built one-third of UC.’”

That calculation, combined with the desire to increase social mobility and provide greater college access for a burgeoning population, resulted in The California Master Plan. Adopted in 1960, the Master Plan essentially made California the first state to, in theory at least, guarantee universal access to higher education. Along with the California State Water Project, the Master Plan became the most enduring part of Pat Brown’s legacy.

n a 1963 speech at Harvard, the Plan’s architect, University of California Chancellor Clark Kerr, described its importance this way: “What the railroads did for the second half of the last century and the automobile for the first half of this century may be done for the second half of this century by the knowledge industry. Knowledge is now central to society. It is wanted, even demanded by more people and institutions than ever before.”3

That observation retains its essential truth nearly six decades later. What has changed, though, is California’s stature in the education firmament. The state’s public colleges and universities remain the nation’s finest, but the days of universal access and free tuition are long gone. So are the days when California’s K-12 schools were among America’s best funded and highest performing. Now, the state typically ranks in the bottom 10 on both measures.

ACT I

The descent can’t be attributed to any single individual, but as a man whose political life — including 16 years in the Governor’s Office — has coincided with this trajectory, a look at Jerry Brown through the lens of education is instructive. Unlike his father, who both benefited from and facilitated California’s ascendancy, Brown has faced enormous headwinds where public finances and public schools are concerned. During his first administration, which lasted from 1975 to 1983, the nation struggled to reconcile the upheaval of the 1960s, the economic malaise of the 1970s and the perpetual American problem of race, ethnicity and integration.

Brown’s challenges as Governor also had a distinctly California flavor that reflected the state’s unique legislative, judicial and electoral character. In Serrano v. Priest, a series of decisions stretching from 1971 to 1977, the California Supreme Court declared the state’s practice of funding school districts primarily through local property taxes an unconstitutional violation of equal protection.

Under the system struck down by the courts, homeowners in low-income areas sometimes paid taxes at higher rates than their wealthier counterparts, even though schools in the poorer neighborhoods typically received lower levels of per-pupil funding. The court ordered the state to remedy those disparities, a charge that was soon complicated by rising anti-tax sentiment.

Property taxes nearly doubled statewide in the mid-1970s and skyrocketing inflation moved people into higher income brackets, adding to their overall tax burden. In his January 1977 State of the State address, Brown acknowledged the issue, noting that, “Obviously, number one on the agenda is property tax. It’s the issue people have been talking about. We need an immediate solution. We also need a long-term solution.”4

“During Gov. Brown’s first administration, California schools were among the best in the nation, with per-pupil spending well above the national average. That began to change as Proposition 13 diminished local and state revenues and resulted in under-investment in the K-12 public education system.”

— Vernon M. Billy, CEO & Executive Director, CSBA

Brown tried to head off the coming tax revolt with a proposal that would provide relief for homeowners whose tax bills consumed an unusually large percentage of their income. He also expressed support for a “split roll” tax that would allow municipalities to tax residential and commercial properties at different rates. That idea has resurfaced in the form of a proposition that will appear on the 2020 ballot, but the idea of split roll couldn’t stem the tide of voter anger over property taxes in the mid-1970s.

Hostility over taxes, changing demographics, and court-ordered rulings on desegregation and school finance created fertile ground for an insurgency led by anti-tax crusader Howard Jarvis. Jarvis was the father of Proposition 13, a measure which reverted assessment to 1975 levels and limited property taxes to 1 percent of assessed value at the time of purchase, with a maximum annual increase of 2 percent to compensate for inflation. Prop 13 passed in June 1978 with 65 percent of the vote, leaving a $4 billion hole (equivalent to about $11.5 billion in 2018) in the budget that had to be backfilled from the state surplus. As a result, school district budgets declined for the first time since the Great Depression and local municipalities across the state reduced services.

“We didn’t really have accountability or standards, those didn’t come in until the nineties,” said former State Superintendent of Public Instruction Jack O’Connell, who is currently a partner with the Sacramento-based public affairs firm Capitol Advisors Group. “His biggest challenge in 1978 when Prop 13 passed was keeping the schools funded and the state afloat with the loss of so much property tax revenue; that took a lot time for him in 1978, ’79 and ’80.”

At the time, Brown was in a close race for re-election with a Republican challenger named Evelle Younger and, tossing aside his initial opposition, embraced Prop 13. He described himself as a “born-again tax cutter,” sponsored a state-income tax reduction that passed the Legislature and was so vigorous in his implementation of Prop 13 that he was nicknamed “Jerry Jarvis.” Brown recovered to win the gubernatorial election in a landslide before making a 1980 presidential bid, but California’s schools have yet to rebound.

“During Gov. Brown’s first administration, California schools were among the best in the nation, with per-pupil spending well above the national average. That began to change as Proposition 13 diminished local and state revenues and resulted in under-investment in the K-12 public education system,” explained Vernon M. Billy, CEO & Executive Director of the California School Boards Association. “Ultimately, the resources and services that California public schools could offer their students declined to the point where, today, we rank at or near the bottom nationally in nearly every significant measure of school funding and staffing. In short, California’s absolute and relative standing in education dropped precipitously between Brown’s first and second turn as Governor.”

Prop 13 provides a line of demarcation between today’s less golden state and the exuberant California that gave birth to the Master Plan, some of the world’s greatest engineering marvels and an iconic lifestyle envied the world over. As Pawel writes in The Browns of California, “The residual impacts of Prop 13 exacerbated the disparities. Affluent communities passed special assessments and bonds to improve their roads, schools, and libraries, while services in poorer communities deteriorated. Blacks and Latinos attended schools that lacked the required courses or quality of teaching to qualify students for admission to the public universities, the traditional route to upward mobility. In 1985, 13 percent of white high school seniors qualified for admission to the University of California, compared to only 4.9 percent of the Latino students and 3.6 percent of the black students. Assessing the situation at a hearing, Assemblymember Tom Hayden said, ‘It appears to me that unwittingly we are evolving into an educational apartheid.’”

ACT II

Deep disparities persisted over the 26 years between Hayden’s remarks and the start of Brown’s second act as Governor. During that time, the divide separating black and Latino students from their white and Asian peers inspired a name — “the achievement gap” — but little in the way of effective action to close it.

When Brown returned to the Governor’s mansion in 2011, the education landscape was vastly different from the one of three decades before. The finance reform of the 1970s had shifted California from a (mostly) local funding system to one where the state controlled the vast majority of school district revenues. Latino students were now a majority in the state’s public schools, having just cracked the 50 percent threshold a few months before Brown took office. Through numerous laws, most notably the No Child Left Behind Act, the federal government had inserted itself into education at the state and local level. Accountability and standards were the watchwords and the era of “high-stakes testing” was in full effect. Public education had become a marketplace of sorts, with the rise of charter schools fueling competition and generating discord between various segments of the education establishment. Where California was once among the most generous states in per-pupil spending, it was now one of the stingiest, languishing at the bottom of the national rankings in both funding and staffing levels — with academic achievement to match. And to top it off, the state was waking up from its recession hangover to find school funding down 20 percent from 2007 — just four years prior.

“During his second term in office, Gov. Brown was charged with serving a student population that was dramatically different from several decades earlier. The state had become far more diverse and inequality had grown, even as the state became far wealthier,” explained Carrie Hahnel, interim co-director at The Education Trust-West. “Gov. Brown chose to fix school funding during his second term, passing the [Local Control Funding Formula] which prioritized equity, but he also demonstrated fiscal conservatism — building a rainy day fund and starting to stabilize our bleeding pension system. In other areas, his views on state overreach in education stayed pretty consistent from his first term to his last. He didn’t think it was the state’s role to reach too far when it came to tracking data or monitoring quality.”

About the only thing that hadn’t changed from Brown’s first term was that poor students still lagged their more affluent counterparts and black and Latino students experienced far worse academic and social outcomes than their white and Asian peers. An increased focus on educational equity and countless reforms and counter-reforms had resulted in some progress, but not enough to provide all students with the basic guarantee of a quality education.

In the time since Hayden characterized California schools as an accidental apartheid, UC eligibility rates had crept upward from 3.6 percent to 6.3 percent for African-American students and from 4.9 percent to 6.9 percent for Latino students. During the same period, UC eligibility rates for white students rose from 13 percent to 14.6 percent, still more than double that of either black or Latino students.

The state’s standardized “STAR” exam produced similar results — overall progress with a stubborn achievement gap. In 2011, 76 percent of Asian students scored at “proficient or above” in English Language Arts, a 21-percentage point increase from 2003. During the same period, white students boosted proficiency rates to 71 percent, an 18-percentage point jump. Meanwhile, less than half of all African-American and Latino students cleared the proficiency bar. Despite a 19-percentage point increase from 2003, just 41 percent of African-American students demonstrated ELA proficiency in 2011. That mirrored results for Latino students who saw a 22-percentage point improvement push proficiency rates to 42 percent.

The story was much the same in math, as 34 percent of African-American students and 40 percent of Latinos met proficiency standards compared to 61 and 72 percent of their white and Asian peers, respectively. Faced with the hydra of a dramatically underfunded public education system, a complex method of allocating those funds, vast differences in resources and opportunity at the district level, and grossly inequitable student outcomes, Brown decided to tackle all three at once.

“It is all too easy for policymakers to approach the education of children in a piecemeal, siloed way; to address the surface issues or symptoms that kids and educators face by proposing a new categorical program or silver bullet, instead of tackling the very systems that give rise to and perpetuate inequity and underachievement,” said Samantha Dobbins Tran, senior managing director of education policy for Children Now, an Oakland-based education advocacy organization. “Gov. Brown took the dysfunction of an irrational, inequitable finance and governance system head on and used his political leadership to fix the way California allocated funding to schools. He did something only a Governor could, and he did it with vision and the full force of his office.”

In 2012, Brown proposed a “weighted student formula” that would increase school funding, simplify the rules governing the distribution of funds and direct more of them to students with higher need. The idea was not new; it had been around in some form for 20 years. A weighted student formula was recommended in both a 2002 update of the California Master Plan and a 2007 report from Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Committee on Educational Excellence. There was broad agreement in Sacramento that the existing system was both unwieldy and illogical. For one, it did a poor job of aligning funding with student need, often providing different amounts of money for each student based on arcane criteria unrelated to the students themselves. In many cases, that resulted in large differences in state funding between districts with virtually identical demographics. Secondly, it funneled money to districts through an opaque system of more than 60 “categorical” funding streams, each one with a specific purpose, narrow restrictions and varying per-pupil allocations. This arrangement limited districts’ ability to allocate funds and design programs suited to their specific circumstances. Yet, even with those shortcomings, no one had been able or willing to reform the broken system.

That began to change in January 2012, when Brown’s budget proposal included a plan to scrap California’s byzantine school funding mechanism for the weighted student formula. That decision set off a frenzy of debate that carried past the legislative session and into the following year, partly because some affluent districts stood to see their state funding reduced under the plan.

“His first attempt was not successful, and it took a two-year effort,” said O’Connell, the former State Superintendent of Instruction. “The additional revenue clearly helped, and Gov. Brown benefitted from having eight years of a strong economy, but he did a herculean job extending the tax brackets [with Proposition 30] that greatly helped fund public education and essential, vital services.

“He focuses on helping poor kids and not just in school, he wants them to have healthy nutrition and he’s committed to health care for all Californians, but particularly prenatal care. If the kid’s not healthy, the kid’s not going to learn, and Gov. Brown gets that.”

In 2012, Brown campaigned for Proposition 30, a ballot measure officially titled Temporary Taxes to Fund Education. The initiative temporarily (from 2013 to 2016) increased the state sales tax a quarter percent to 7.5 percent. It also raised income tax rates on individuals earning more than $250,00 a year, a measure voters extended through 2030 when they approved Proposition 55 in 2016. The passage of Prop 13 was expected to generate nearly $5 billion in 2013-14 and that gave the Governor additional room to maneuver.

In 2013, Brown submitted a reworked proposal with a “hold harmless” provision guaranteeing that no district would receive less money under the new school funding plan than it had previously. That concession, among others, secured approval through passage of the 2013-14 budget and Assembly Bill 97. The new system was dubbed the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) because it freed schools districts from the yoke of categoricals and gave them the flexibility to use funds in the manner they felt would best improve outcomes for the targeted student groups. Under LCFF, schools with large percentages of high-need students — defined as low-income students, English learners, foster youth and homeless students — would receive additional allocations on top of the base grants received by almost every district in the state. Specifically, districts and county offices of education receive a “supplemental grant,” an additional 20 percent of the base per-pupil allocation for each high-need student. Districts also get a “concentration grant” if high-need students account for more than 55 percent of their student population.

“A major part of Gov. Brown’s legacy is the implementation of the Local Control Funding Formula. He believes, as I do, that decisions are best made at the local level, by the people who know their districts best,” said Assemblymember Patrick O’Donnell (D-Long Beach), chair of the Assembly Education Committee. “LCFF provides district leaders, school board members, parents and school staff with the ability to collaborate and determine their priorities for funding, while holding the locals accountable for student achievement.”

In return for the funding and flexibility, school districts must engage parents, staff and community in developing a Local Control Accountability Plan for approval by the school board and review by the county office of education. The LCAP is a three-year plan that establishes goals in eight priority areas that fall under the heading of engagement, conditions of learning and pupil outcomes. The LCAP also indicates the programs and strategies that will be used to boost outcomes for high-need students. While LCAPs have the potential to increase community investment in schools and make districts more responsive to the needs of students, staff and families, they remain a point of contention five years into LCFF. Some districts have developed robust plans that involve stakeholders and clearly map out how the money would be used to benefit students, but execution varies greatly. Also, in certain districts, the sheer size and complexity of the document itself has discouraged stakeholders from engaging.

“I have been disappointed by the Brown administration’s consistent unwillingness to provide effective transparency on how funding is spent, whether students are receiving essential supports, and if gaps in achievement are closing over time,” Children Now’s Tran said. “When this information has been painstakingly gathered at various points in time and analyzed, it is clear there are vast inequities in California. The first step in addressing these inequities is to consistently shine a light on them and then ensure that communities have the tools and supports they need to address them.”

Brown’s appointees have been sensitive to this criticism, even if their efforts to address it haven’t always been well received. Every year since the introduction of LCFF and the LCAP, the State Board of Education and the California Department of Education have made tweaks, if not wholesale changes to portions of the accountability system to improve clarity and transparency. As Mike Kirst, the outgoing president of the State Board of Education and the intellectual font of Brown’s education policies wrote in a 2015 op-ed for EdSource, “A massive shift in decision-making, planning and resource allocation requires patience, persistence and humility. It requires us to be mindful that many of the system components are still evolving. In the meantime, I am encouraged about how the funding formula reforms are moving decision making closer to where it should have been all along — closer to where children are learning and teachers are teaching.”

Fierce advocacy for local control has been a hallmark of Brown’s second turn in the Governor’s office. Along the way, he has popularized — at least in legislative and policy circles — the word subsidiarity, a term which harkens back to his days in seminary. Subsidiarity is a principle of the Catholic church which holds that decisions should be made at the lowest level possible for effective administration. Brown’s commitment to subsidiarity was strengthened during his time as mayor of Oakland from 1999 to 2007. Working in a municipal executive role for the first time, Brown chafed under one-size fits all dictates from Sacramento. When he returned to the Governor’s mansion four years later, he would regularly veto bills on the grounds that the matters were better addressed at the local level, a trait that endeared him to school boards across the state.

“With unfortunate exceptions, like the Reserve Cap and decision to withhold $7 billion worth of voter-approved school bond funds – money that could have been used to build new schools and modernize old ones– Gov. Brown has upheld the principle of local control,” CSBA’s Billy said. “Gov. Brown often vetoed legislative bills that sought to encroach on the rights of democratically-elected school boards. In many instances, the Governor halted efforts at micromanagement from the Legislature and empowered those who know their communities best to perform the work that voters elected them to do.”

Brown’s time in Oakland not only reinforced his belief in local control, it also deepened his interest — and involvement — in the city’s local schools. While mayor, he was able to change the charter and temporarily add three appointees to the traditionally seven-member Oakland Unified School District school board. The district soon fell into receivership and the state assumed control, but Brown achieved a more durable victory when he founded a pair of charter schools, the Oakland Military Institute and the Oakland School of the Arts. (In a departure from local control, OMI was initially voted down by the local and county school boards before Brown’s former chief of staff and then-Gov. Gray Davis interceded to help win approval from the State Board of Education — the first time it ever approved a charter.)

Brown envisioned OMI as a place that would recreate the rigor and structure of the St. Ignatius he knew four decades before and inspire a love of learning. Where education is concerned, inspiration is a recurring theme for Brown who can seem ambivalent about the whole enterprise, or at the least the way it’s currently practiced.

Legacy

Brown likes to share a story about an exam he took in his youth which had just one question: “Write your impression of a green leaf.” At a 2013 event in Silicon Valley documented by The Atlantic reporter Emma Green, Brown admitted he was stumped by the question and still ponders it to this day. “This is a very powerful question that has haunted me for 50 years, but you can’t put that on a standardized test. There are important questions that can’t be captured in tests.”5 The speech was designed as an opportunity for Brown to discuss his thoughts on Common Core, but was also a meditation on the limits of formal, standardized education. That kind of certainty about the uncertainty of things is characteristic for Brown, even when discussing his major achievements. In a 2016 interview with CALmatters’ Judy Lin, Brown even downplayed the ability of LCFF to make a dent in the achievement gap, telling her, “It’s pretty hard to do. Even in the same family there are pretty close differences. Look, I wouldn’t measure it in some perfect sameness involving people of all backgrounds. But rather it’s giving people a boost who are coming into school with experiences that don’t lend themselves as much to mastering the material as other people.”

“The gap has been pretty persistent,” he continued. “So, I don’t want to set up what hasn’t been done ever as the test of whether LCFF is a success or failure. I don’t know why you would go there. Since we did the Academic Performance Index (an earlier, now abandoned metric for measuring school performance) I think the achievement level increased substantially for everybody at about the same rate. So, the gap would not change but there was definite improvement.”6

CSBA’s Billy points out that LCFF overlooks hundreds of thousands of students — primarily African-American and Latino — who are not classified as low-income or English Learner, but still perform below standard on the state’s ELA and math exams. He suggests that allocating more funds to these struggling students would better realize the Governor’s intent of directing money where need is greatest, and in so doing, help close opportunity and achievement gaps. Billy adds that the achievement gap has remained intact, at least in part, because schools aren’t getting the resources needed to level the playing field. Rising costs, including the skyrocketing pension contributions in which Brown has played a role, are eroding much of the gains made under LCFF. As expenses for transportation, utilities, special education and health care climb rapidly, Billy argues that 2007-level funding is not enough to close gaps while preparing all students for an increasingly global, complex and technological world. And he’s not alone in that belief.

“Gov. Brown has been true to his word and affirmed his belief in local control by vetoing those legislative bills that sought to encroach on the right of democratically elected school boards to determine how to meet the needs of students and the community who voted them into office. ”

Vernon M. Billy, CEO & Executive Director, CSBA

“We may have met the self-imposed target for LCFF funding this year, but more resources are needed,” said Assembly education chair O’Donnell. “Students have diverse needs that classroom teachers cannot address. Our challenges are to work with [incoming] Gov. Newsom to maintain LCFF and increase funding for our schools.”

Eastin, the former state superintendent of instruction, sees returning funding to pre-recession levels as a step in the right direction, but not nearly enough to make up for decades of neglect or California’s place near the bottom of the school funding tables.

“Why hasn’t he begun a campaign to make changes in Prop 13, especially as it relates to large industrial properties that are not being reassessed even as 50 percent of stockholders are turning over?” Eastin asked. Eastin is generally complimentary of Brown’s leadership, praising his work on fiscal stability and the environment, but calls education his “weak spot” saying that “he hasn’t been a warrior for public education; proof is we’re in the bottom 10 in funding and money matters.”

“Local companies ought to be paying taxes and it ought to be routinely done,” Eastin continued. “What you have now is people living next door and one paying much more than the other, but it’s much more dramatic when it comes to commercial and many companies are paying property tax that’s pretty much what they were paying 40 years ago. It’s not okay to say your hands are tied, you can mount a ballot measure to change things and he’s not shown much initiative in that area.”

Conversely, Brown’s supporters argue that people overlook the difficulty in getting Prop 30 and Prop 55 passed, measures that added billions to public school coffers. They also think observers underrate the transformative nature of LCFF and how, for the first time, it changed the philosophical framework of school finance to align funding with need.

“Together we have helped our districts implement the Local Control Funding Formula, which gives local school boards more discretion over spending, requires more local participation and provides more resources to those who need them most — English learners, foster youth and those from low-income families,” said State Superintendent of Instruction Tom Torlakson. “We have also worked hard to implement Common Core standards in math and English that emphasize analytical skills, critical thinking, and communications skills. In addition, we have introduced new, online tests, called Smarter Balanced, to analyze the progress our students are making.

“Our work has paid off. High school graduation rates have reached an all-time high of 83 percent, suspensions and expulsions have declined; and eligibility for University of California and California State University enrollment have increased; particularly for Latino and African-American students.”

There are some early indications that Brown’s signature funding formula is making a difference. Rucker C. Johnson, associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy and Sean Tanner of the Learning Policy Institute (and now with WestEd), documented this progress in Money and Freedom: The Impact of California’s School Finance Reform on Academic Achievement and the Composition of District Spending.

“We find that LCFF-induced increases in school spending led to significant increases in high school graduation rates and academic achievement, particularly among poor and minority students. A $1,000 increase in district per-pupil spending experienced in grades 10-12 leads to a 5.9 percentage-point increase in high school graduation rates on average among all children, with similar effects by race and poverty,” Johnson and Tanner wrote. “On average among poor children, a $1,000 increase in district per-pupil spending experienced in eighth through 11th grades leads to a 0.19 standard deviation increase in math test scores, and a 0.08 standard-deviation increase in reading test scores in 11th grade. These improvements in high school academic achievement closely track the timing of LCFF implementation, school-age years of exposure and the amount of district-specific LCFF-induced spending increase. In sum, the evidence suggests that money targeted to students’ needs can make a significant difference in student outcomes and can narrow achievement gaps.”

While it may it not be a tangible monument like a gleaming new UC campus, the impact of providing more opportunity for the state’s 6.2 million public school students is a considerable accomplishment.

“He recognized the need for systemic changes and fundamentally altered how California funds our school districts,” said Ed-Trust West’s Hahnel. Hahnel, like Tran of Children Now, is critical of Brown’s inability to implement data systems that could more effectively measure the impact of his reforms, noting that, “In some ways, the extent of Brown’s legacy when it comes to California schools won’t be fully understood until we’re able to adequately measure how students are doing, K through college.”

Regardless of the verdict, it’s clear that Brown’s time in office was incredibly consequential for public schools, both as a wunderkind Governor and now as a philosopher-statesman in the manner of his muse Cicero.

“Many education advocates can quote verbatim the part of his state of the state speech where he introduced LCFF, saying ‘equal treatment for children in unequal situations is not justice,’” Hahnel said. “LCFF didn’t just change how we fund schools, it changed how we’re supposed to think about making funding decisions. Shifting to such an emphasis on local control meant education politics in California has been a different beast than perhaps ever before.”

Troy Flint is CSBA’s Senior Director of Communications

Endnotes

- Miriam Pawel, The Browns of California (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), 91.

- Ibid, 70.

- Ibid., 106

- Ibid., 268

- Emma Green, “Jerry Brown: Latin Scholar and One-Time Almost Priest,” The Atlantic, December 17, 2013, www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2013/12/jerry-brown-latin-scholar-and-one-time-almost-priest/282426/

- Judy Lin, “Jerry Brown on subsidiarity, meritocracy and fads in education”. CALmatters, April 5, 2016, calmatters.org/articles/jerry-brown-on-subsidiarity-meritocracy-and-fads-in-education/