Closing the college-going gap

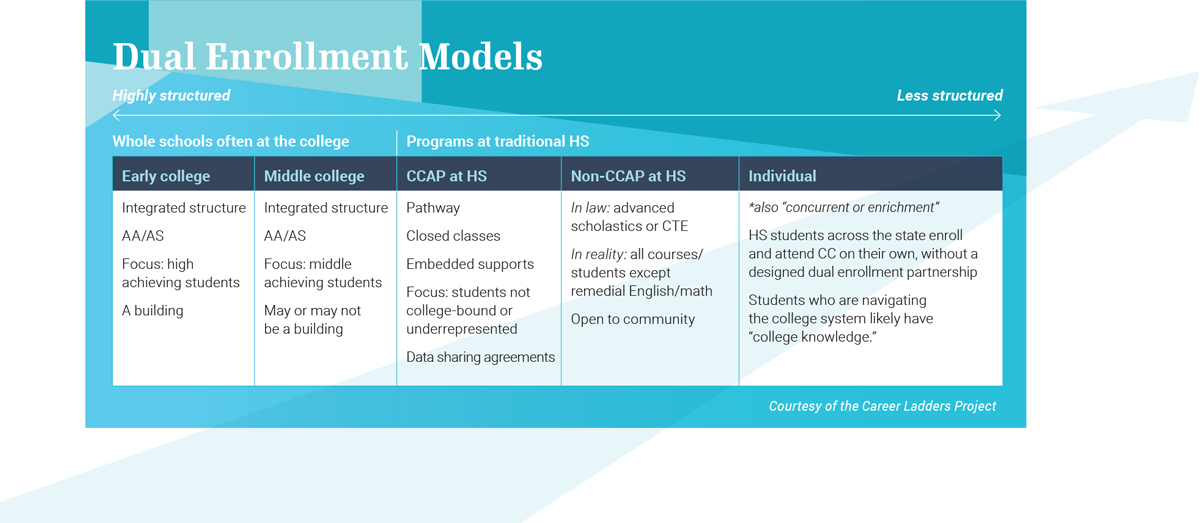

Dual enrollment opportunities range from students who take college courses independently, also called concurrent enrollment, to early college high schools to formal agreements between colleges and school districts enabled by laws adopted in the last 10 years.

istorically, those students taking college courses independently were often not a very diverse group of students,” said Michal Kurlaender, professor and department chair at the UC Davis School of Education and lead researcher for Wheelhouse: The Center for Community College Leadership and Research. “They were disproportionately white, Asian and higher-income students. The motivation for new legislation that expanded dual enrollment programs was to ensure that that opportunity was before all types of students, because it was so underutilized by underrepresented students.”

While dual enrollment is not a new concept in California, a focus on using it as a lever for providing an equitable education is.

California’s history

In 2015, to expand access to college dual enrollment courses, former Gov. Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 288, establishing the College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP) partnership, which allows community college districts to partner with K–12 districts in offering college classes exclusively to high school students on high school campuses. AB 288 aims to provide dual enrollment opportunities to students who “may not already be college bound or who are underrepresented in higher education.”

Two additional bills — Senate Bill 379 (2013) and AB 413 (2019) — codified early and middle college high school programs, which allow students to earn both a high school diploma and up to two years of college credits, and are usually located on or near the college campus. Like AB 288, AB 413 specified that middle college high schools in particular provide a college and career curriculum to students who are underrepresented in college — especially those who “are performing below their academic potential.”

The Career Ladders Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the college-going rate and opportunities for underrepresented students, emphasizes the impact that dual enrollment programs can have on a student’s mindset and achievement outcomes.

“For first-generation students in particular, participating in dual enrollment leads them to graduate high school at a higher rate than their peers, go on to post-secondary at a higher rate and complete college more quickly than their peers who have not experienced dual enrollment,” said Career Ladders Project Senior Director Naomi Castro. “There are also quite a few studies, and the evidence is always mounting, that students from populations that are underrepresented in higher education may actually benefit more. So, they see higher gains in all of those areas of success in high school graduation, in persistence, in matriculation and completion of post-secondary.”

California’s current landscape

Dual enrollment aligns with the California Community College (CCC) system’s Vision for Success, a set of goals and commitments that include increasing the numbers of students earning degrees or certificates and transferring to a University of California or California State University campus. Integral to this work is the CCC’s Guided Pathways, an equity-focused framework intended to provide clear paths for students and remove systemic obstacles to their success. Guided Pathways is a structure to provide all students with clear enrollment avenues, course-taking patterns and support services. CCC sees dual enrollment as an extension of Guided Pathways.

“When we think about the goals of the Vision for Success and Guided Pathways, it’s just a natural synergy with dual enrollment,” said Aisha Lowe, CCC vice chancellor for Educational Services and Support. “There is a focus on really wanting to see dual enrollment shift to being an equity gap closing strategy, focusing on targeting dual enrollment toward low-income students and students of color and students who may traditionally have been left out of higher education. There’s clear alignment with the goals of the Vision for Success around closing equity gaps — it’s about how we build pathways from high school into the community colleges and then into industry, or from high school into the community colleges and then off to a four year, in a way that is very purposeful, strategic and guided.”

“For first-generation students in particular, participating in dual enrollment leads them to graduate high school at a higher rate than their peers, go on to post-secondary at a higher rate and complete college more quickly than their peers.”

CCC is partnering with Career Ladders Project to explore and build out these pathways and agreements through a Dual Enrollment Community of Practice with five colleges and their high school partners, which will focus on professional development trainings and workshops and developing resources and tools.

“This Community of Practice is one of the strategies that we use to then try to transition things from ideas and vision into actual implementation,” said Lowe. “It’s following up on how we can bring the strategic framework to life so there’s not just a vision and a set of ideas. How do we get a small group of colleges actually working on how they can transition their dual enrollment offerings to be more pathways based and directed, providing students that hands-on support that they need to be able to begin their college career in high school.”

“There is a focus on really wanting to see dual enrollment shift to being an equity gap closing strategy, focusing on targeting dual enrollment toward low-income students and students of color and students who may traditionally have been left out of higher education.”

Dual enrollment in action

“What the early college program did at Bakersfield College was take existing dual enrollment courses and partnerships and transform the thinking from what we like to call ‘random acts of dual enrollment’ to connecting every college course that a high school student takes to a certificate and/or degree completion pathway,” said Kylie Campbell, Early College director for the Kern County Community College District (CCD), of which Bakersfield is a part. “I think Bakersfield had a leading role in making sure they connect the pathways and having high school students graduate from the program with associate degrees.”

Kern CCD includes three community colleges that together partner with about 40 districts. There are currently no CCAP agreements, however, Campbell thinks that the newest legislation will be helpful in beginning to create partnerships under the framework. AB 102 removes the provision that prohibited an oversubscribed community college course from being offered as part of a CCAP partnership and removes the 10 percent cap of full-time equivalent students claimed as special admits by community colleges for purposes of apportionment — both issues that impacted dual enrollment at Kern CCD.

“We have very strong MOUs and partnerships already, so it really is a matter of having conversations to solidify those pathways,” Campbell said. “The benefit being that we have a very high number of students who are maxing out at 11 units right now — when you’re non-CCAP, that’s the maximum you can take. But with a CCAP agreement, you can go up to 15.”

“The dual enrollment program is an added advantage in the college admissions process by preparing students for the rigors of college coursework and awarding credits that count towards a degree,” said Kern HSD board Vice President David Manriquez. “It is also an important way to expand educational opportunities, improve economic mobility and meet California’s workforce needs.”

Early successes from the program are promising, with Kern CCD data showing that students who participate in dual enrollment courses have a 90 percent success rate in completing the course compared to a 67 percent success rate for traditional Kern CCD students. This success early on is vital to students’ outcomes later in their academic careers.

“When students complete a college course while in high school, they begin to envision themselves as a college student,” said Dean McGee, Kern HSD deputy superintendent of Educational Services and Innovative Programs. “This is especially powerful for students who may not have ever envisioned college in their future.”

Approximately 90 percent of all high school students enrolled in Bakersfield College’s early college courses are students of color, and the equity outcomes for these students are notable, according to a 2021 research analysis of the program. Participating African American and Latino high school students who complete college courses successfully far exceeds the average course success rates for African American and Latino traditional Bakersfield College students. For Latino early college students, average course success rates between 2014–15 and 2017–18 ranged from 88 percent to a high of 92 percent compared to the Latino traditional Bakersfield College student average of 67 percent. For African American early college students during the same time period, success rates ranged from 73 percent to 91 percent compared to the traditional Bakersfield College African American student average of 52 percent.

At McFarland High School, located about 30 miles from Bakersfield College and seven miles from its Delano campus, all students starting in ninth grade may complete between nine and 60 units during high school toward a certificate, degree or transfer to a four-year institution. The student population is about 97.7 percent Latino and majority low income.

“This year will be our first graduating senior class of the true early college model,” said Brian Bell, McFarland USD assistant superintendent and former principal at McFarland High School. “Every single student at McFarland High School, when they graduate, will have a minimum of nine units of college credit. Forty students this year are graduating with their AA degree — think of the financial impact to them and their family. Even more so, they will be able to hit the ground running in a direction they’ve been able to build.”

In addition, teaching a college-level dual enrollment course requires a master’s degree, and it typically needs to be specialized to the subject matter. While a decent number of McFarland teachers had master’s degrees, they were in education, therefore only qualifying them to teach in an education pathway. The shortage was primariliy addressed when Bell and McFarland administrative staff surveyed existing teachers for colleague recommendations and attended job fairs to talk to as many candidates as possible.

“There’s really no stopping these students once all of the systems are in place to guide and support them,” said Bell.

Support

“It’s about data, data, data,” CMEC’s Balian said. “You’ve got to monitor these students and you’ve got to give them strong support. You cannot expect a kid to walk into a college class and be successful without a support system. You can have student supports through programs like AVID, some schools create a little seminar, some will do tutorial sessions during lunch and make it mandatory if the kid is not doing well. So, there’s different ways to do your student support, but you have to plan for that. If you have strong partnerships, good pathways, strong student support and monitor your data, you’ve got a good chance of having a successful program.”