Summer 2019

Achievement gaps among Asian American students

by Kimberly Sellery

by Vernon M. Billy

by Sepideh Yeoh, Arati Nagaraj and Steve Ladd

by Kathryn Meola

By Barbara Nemko

By Jennifer Franka

Interview with Ellie Householder

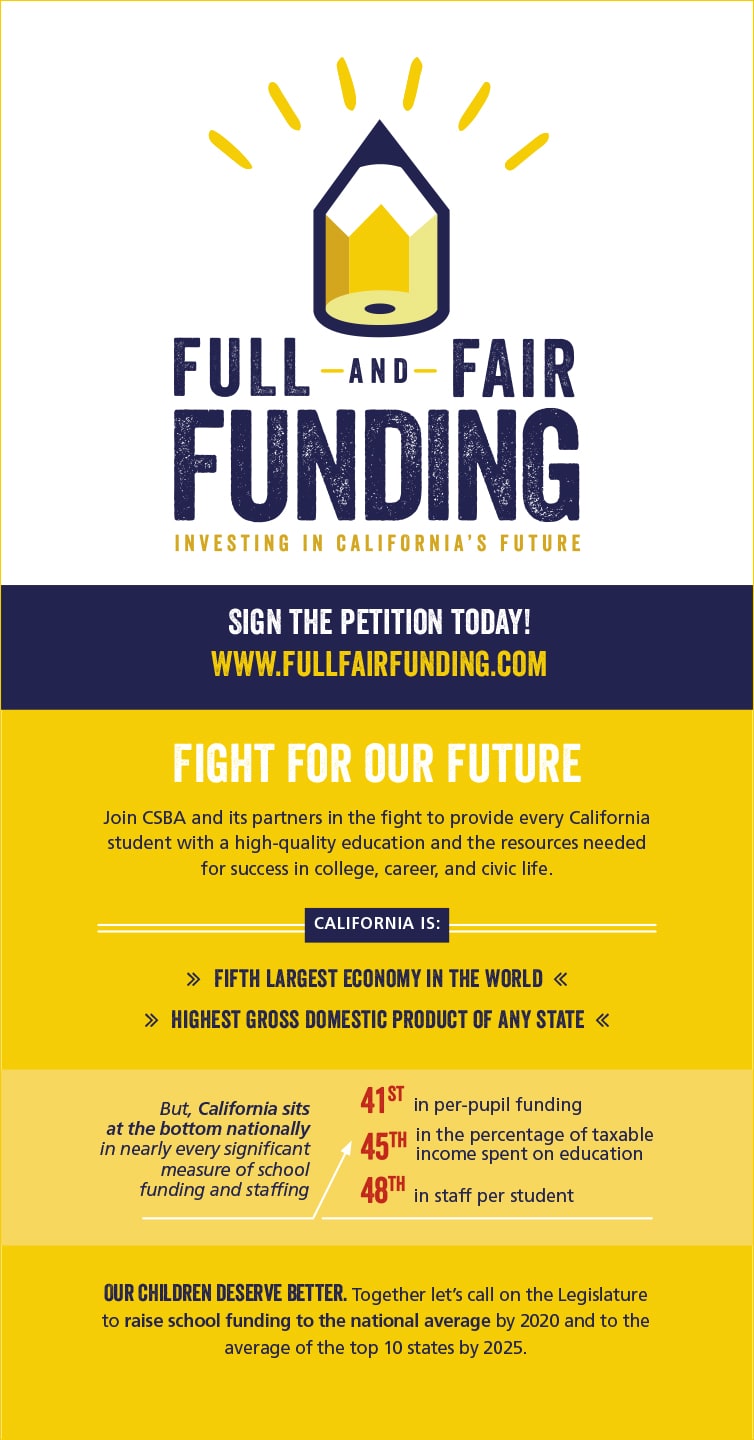

n my last CEO’s note in the spring California Schools magazine, I discussed the ongoing “big short” in how the state of California has funded its schools over the past several decades.

A new statewide poll from CSBA confirms that, in a year when statewide teacher strikes persist and the financial strain of our schools becomes more prevalent in the California news cycle, the general public is also acutely aware of the funding crisis facing our schools.

What is often viewed as the “silent recession” encroaching on our schools has been distressingly obvious for more than a decade to those closely tied to the inner workings of public education. As the state’s economy and revenues have swelled, so have the level of unfunded state mandates and costs to operate schools. These types of expenses have deflated district and county office of education budgets and have continually forced our schools to do more with less.

Region 1, Del Norte County US

Sherry Crawford

Region 2, Siskiyou COE

A.C. “Tony” Ubalde, Jr.

Region 3, Vallejo City USD

Paige Stauss

Region 4, Roseville Joint Union HSD

Alisa MacAvoy

Region 5, Redwood City ESD

Darrel Woo

Region 6, Sacramento City USD

Yolanda Peña Mendrek

Region 7, Liberty Union HSD

Matthew Balzarini

Region 8, Lammersville Joint USD

Region 9, Atascadero USD

Susan Markarian

Region 10, Pacific Union ESD

Suzanne Kitchens

Region 11, Pleasant Valley SD

William Farris

Region 12, Sierra Sands USD

Meg Cutuli

Region 15, Los Alamitos USD

Karen Gray

Region 16, Silver Valley USD

Katie Dexter

Region 17, Lemon Grove SD

Wendy Jonathan

Region 18, Desert Sands USD

Region 20, Santa Clara USD

Kelly Gonez

Region 21, Los Angeles USD

Nancy Smith

Region 22, Palmdale SD

Helen Hall

Region 23, Walnut Valley USD

Donald E. LaPlante

Region 24, Downey USD

Crystal Martinez-Alire

Director-at-Large American Indian,

Elk Grove USD

Gino Kwok

Director-at-Large Asian/Pacific Islander,

Hacienda La Puente USD

Director-at-Large African American,

Monterey Peninsula USD

Heidi Weiland

Director-at-Large County, El Dorado COE

Joaquín Rivera

Director-at-Large Hispanic, Alameda COE

Dana Dean

CCBE President, Solano COE

Chris Ungar

NSBA Director, San Luis Coastal USD

How do you create a collaborative board culture that minimizes micromanaging and dominating of the meetings by the board president?

Sepideh Yeoh: Developing an understanding of what constitutes a collaborative board culture and how it will contribute to an effective governance team is the first step. Collaboration can be defined as individuals coming together to create something that will create purpose. For boards, this “something” is a unity of purpose that will support the board in achieving the district or county office of education’s visions and goals. Once your governance team agrees upon your unity of purpose, the groundwork for establishing a foundational pillar is set.

Troy Flint, tflint@csba.org

Managing Editor

Kimberly Sellery, ksellery@csba.org

Marketing Director

Serina Pruitt, spruitt@csba.org

Staff Writers and Contributors

Hugh Biggar, hbiggar@csba.org

Andrew Cummins, acummins@csba.org

Aaron Davis, adavis@csba.org

Graphic Design Manager

Kerry Macklin, kmacklin@csba.org

Senior Graphic Designer

Mauricio Miranda, mmiranda@csba.org

Circulation and Advertising

csba@csba.org

Emma Turner, La Mesa-Spring Valley SD

President-elect

Xilonin Cruz-Gonzalez, Azusa USD

Vice President

Tamara Otero, Cajon Valley Union SD

Immediate Past President

Mike Walsh, Butte COE

CEO & Executive Director

Vernon M. Billy

Articles submitted to California Schools are edited for style, content and space prior to publication. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent CSBA policies or positions. Articles may not be reproduced without written permission of the publisher. Endorsement by CSBA of products and services advertised in California Schools is not implied or expressed.

he California Public Records Act requires that all public agencies respond to requests for documents by the public, unless an exemption applies. One such exemption is personnel records; however, a common misperception is that all personnel files are exempt from disclosure.

houghts of the Napa Valley often bring to mind acres of beautiful vineyards, upscale restaurants and spa retreats. While its beauty is undeniable, Napa is also home to many low-income families. About one-third of Napa’s population is Hispanic or Latino, and more than half of all children in Napa County’s public schools are Dual Language Learners. In addition, 42 percent of Napa’s preschool-age children are living in poverty.

Research has shown that at-risk children typically hear 30 million fewer words by age 4 than their more affluent peers. They enter kindergarten with only 25 percent of the vocabulary they need to succeed and most of them never catch up.

In an effort to level the playing field, the Napa County Office of Education and NapaLearns, a nonprofit fundraising organization, began a 2011 summer pilot project that grew into a major countywide Digital Early Learning initiative to increase early literacy opportunities for every preschool age child in Napa County.

class act: Best practices in action

class act:

Best practices in action

class act:

Best practices in action

t a time when many school campuses are silent for the summer, each elementary school in the Lake Elsinore Unified School District has a classroom bustling with activity, as small groups of students move between reading, writing and technology centers at the district’s Summer Literacy Camps.

Winner of a prestigious 2018 CSBA Golden Bell Award, the summer camps serve more than 800 elementary students who are six months to one year behind in reading when entering grades 1, 2 and 3. The Lake Elsinore USD board of trustees charged Assistant Superintendent Alain Guevera with creating the program. He said the focus on these early grades sets kids up for a foundation of success. “Research shows that if kids can’t read really well by third grade, they really struggle with the rest of their academic career.”

In fact, according to the Campaign for Grade-Level Reading — a network of national and local civic leaders, policymakers, advocates and community organizations with the aim of improving early reading comprehension — reading proficiency by third grade is the most important predictor of high school graduation and career success.

t’s a July afternoon in Long Beach and 100 people have gathered as a group of 11- and 12-year-olds take a STEAM challenge. A crowd of families, educators and elected officials have come to cheer on students as they race rowboats in Alamitos Bay.

These aren’t your everyday rowboats; these boats are handmade with only cardboard and duct tape and are designed to hold four students. The students have spent weeks creating them, practicing science, technology, engineering, art and math — a collection of subjects commonly known as STEAM. Most of the boats will sink in the harbor, but that’s not bothering the students — they’ve grown used to pushing themselves. Just earlier in the day, the students raced sailboats. With no adults. They are feeling like they can do anything.

The activity is part of the Summer STEAM Institute, a no-cost camp where the motto is perseverance. The students, all from low-income households, have spent the last three weeks doing hands-on projects and practicing 21st-century skills like risk taking and communication. The race is the culminating project of their work on these rowboats, which has included designing 3D-printed models, engineering prototypes, scaling them up to fit four people and building the final boats.

What inspired you to become a school board member?

I am a product of Antioch USD and I have a deep love for my community. I also understand that in order to love something, you have to be willing to admit when things aren’t working. Currently, more than 50 percent of Antioch USD students are not meeting standards in math and reading, and nearly 70 percent of our students are not graduating with UC/CSU requirements met. This reality of our current shape of Antioch USD motivated me to step up, get involved and begin dismantling a system that effectively prevents all of our community’s children from being successful, regardless of their background.

List three books that have left a lasting impression on you.

Night by Elie Wiesel, Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur and Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire.

Who was one adult you looked up to as a child and why?

My great grandmother, Ally Geraldine, who I called “Nana.” She grew up in Dust Bowl Texas, worked in the factories in World War II, and, despite the odds, did everything possible to provide for our family as a single mother, grandmother and great-grandmother. She loved and nurtured me, and helped me build strength and confidence.

Who/what inspires you as an adult?

My 3-year-old nephew, Malakai, and the future we’re leaving for him and his generation. Decades from now they will know whether or not we gave them the opportunity to thrive and succeed academically. Access to quality education and economic well-being were things that my generation was promised, yet largely went unmet. I know Malakai will depend on what me and other like-minded public servants do today to ensure we are leaving this world a better place than we received it.

What unique perspective do you bring to the board as Antioch USD’s youngest-ever board member?

As a millennial public servant, I lived through the devastating impacts of the Great Recession. The way things have “always been done” didn’t work for many of us, and as a result, both our individual and collective perspectives have been shaped by an idea that it’s time do things differently, fairly and equitably. I approach policy and emerging issues with an open mind, by actively listening and by being willing to challenge conventional wisdom.

How do you fill your time when not performing board duties?

In addition to my school board duties, I am also a graduate student at the Goldman School of Public Policy, a graduate student instructor at UC Berkeley and a delegate to the California Democratic party. When I am not working or in school, I spend my days with my family, reading, researching, writing and advocating for just and equitable policies that meet the needs of all members of our community. I constantly surround myself with family, love, education and community in any way possible.

What inspired you to become a school board member?

I am a product of Antioch USD and I have a deep love for my community. I also understand that in order to love something, you have to be willing to admit when things aren’t working. Currently, more than 50 percent of Antioch USD students are not meeting standards in math and reading, and nearly 70 percent of our students are not graduating with UC/CSU requirements met. This reality of our current shape of Antioch USD motivated me to step up, get involved and begin dismantling a system that effectively prevents all of our community’s children from being successful, regardless of their background.

List three books that have left a lasting impression on you.

Night by Elie Wiesel, Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur and Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire.

Who was one adult you looked up to as a child and why?

My great grandmother, Ally Geraldine, who I called “Nana.” She grew up in Dust Bowl Texas, worked in the factories in World War II, and, despite the odds, did everything possible to provide for our family as a single mother, grandmother and great-grandmother. She loved and nurtured me, and helped me build strength and confidence.

Who/what inspires you as an adult?

My 3-year-old nephew, Malakai, and the future we’re leaving for him and his generation. Decades from now they will know whether or not we gave them the opportunity to thrive and succeed academically. Access to quality education and economic well-being were things that my generation was promised, yet largely went unmet. I know Malakai will depend on what me and other like-minded public servants do today to ensure we are leaving this world a better place than we received it.

What unique perspective do you bring to the board as Antioch USD’s youngest-ever board member?

As a millennial public servant, I lived through the devastating impacts of the Great Recession. The way things have “always been done” didn’t work for many of us, and as a result, both our individual and collective perspectives have been shaped by an idea that it’s time do things differently, fairly and equitably. I approach policy and emerging issues with an open mind, by actively listening and by being willing to challenge conventional wisdom.

How do you fill your time when not performing board duties?

In addition to my school board duties, I am also a graduate student at the Goldman School of Public Policy, a graduate student instructor at UC Berkeley and a delegate to the California Democratic party. When I am not working or in school, I spend my days with my family, reading, researching, writing and advocating for just and equitable policies that meet the needs of all members of our community. I constantly surround myself with family, love, education and community in any way possible.

Would you like to participate in an upcoming Member Profile? Contact us at editor@csba.org.

Bust

Enrollment

Adds New

Challenges

for California

Schools

Bust

Enrollment

Adds New

Challenges

for California

Schools

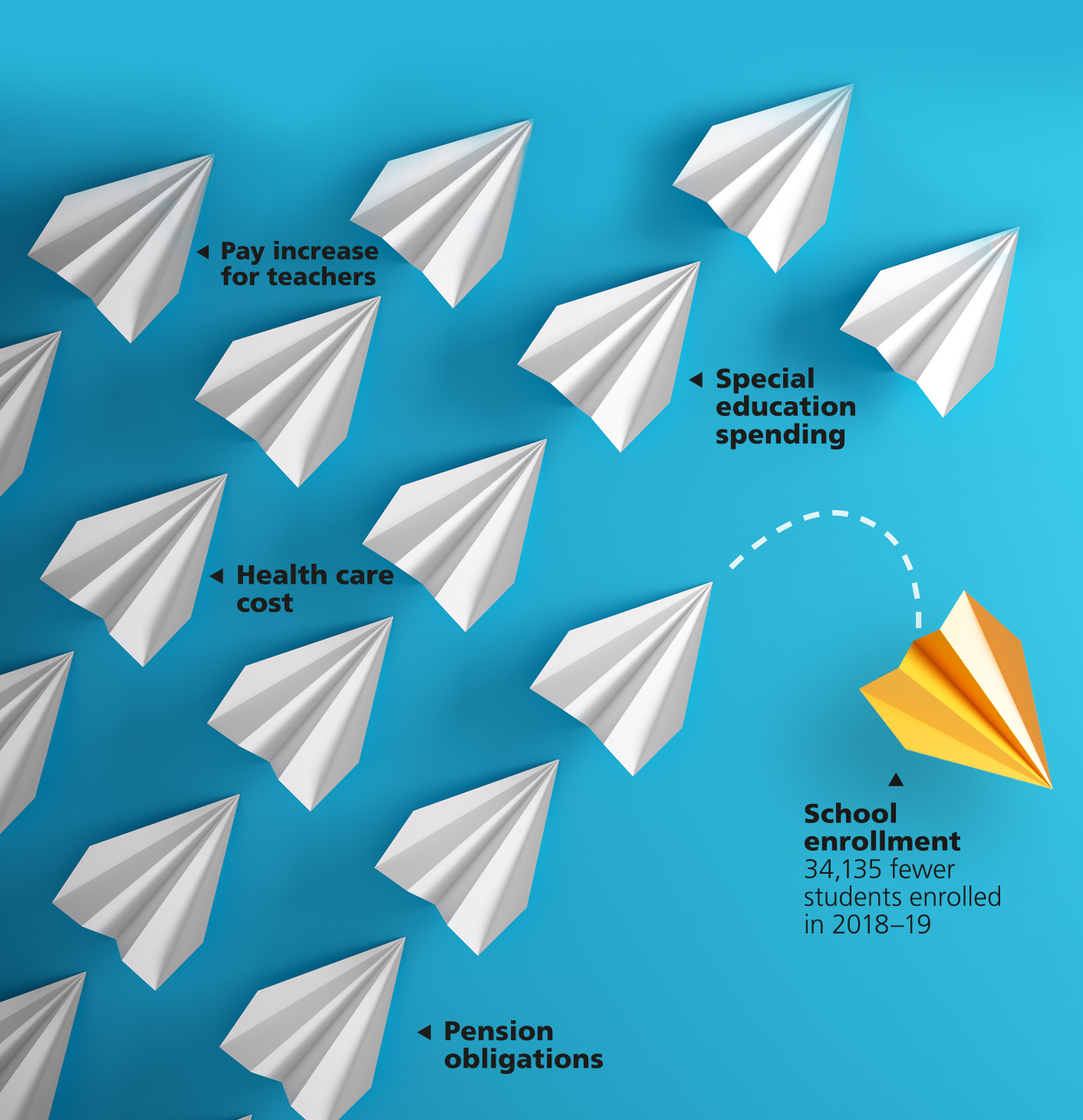

n recent years, California’s birth rates have flatlined as families are increasingly delaying having children or moving out of the state in search of lower costs of living and affordable housing. These population changes are now hitting cash-strapped California school districts already facing rising costs, increased pension obligations and chronically low state funding. How to balance these entangled demographic and financial pressures without sacrificing educational services and quality is a pressing issue for many districts, one that LAUSD and others are hoping to transform from a potential crisis into an opportunity.

According to the latest statistics from the California Department of Education, 34,135 fewer students enrolled in the state’s K-12 public schools in 2018–19 compared to the year before. In the past five years, enrollment has dropped by 0.8 percent, from 6,235,520 in 2014–15 to 6,186,278 in 2018–19. As a result, about half of the state’s nearly 1,000 districts have experienced enrollment losses.

The situation is especially prevalent in California, which served 113,000 immigrant students in the 2017 – 18 school year, according to California Department of Education data. The number marks a dramatic rise from 2014 – 15, when 65,609 immigrant students were enrolled. In issuing April 2018 immigration guidance to schools, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra said about 250,000 undocumented children ages 3-17 are enrolled in the state’s public schools and 750,000 K-12 students in California have an undocumented parent.

The situation is especially prevalent in California, which served 113,000 immigrant students in the 2017 – 18 school year, according to California Department of Education data. The number marks a dramatic rise from 2014 – 15, when 65,609 immigrant students were enrolled. In issuing April 2018 immigration guidance to schools, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra said about 250,000 undocumented children ages 3-17 are enrolled in the state’s public schools and 750,000 K-12 students in California have an undocumented parent.

urther, more than 28,000 children who have crossed the U.S. border without their parents since 2014 are estimated to be living in California. Most of these unaccompanied minors reside in Alameda and Los Angeles counties. In the Oakland Unified School District alone, schools served 2,862 newcomer students in 2017–18, defined by the district as those who have been in the U.S. less than three years and who speak a language other than English at home.

With immigration policy debates shifting by the day and population trends often difficult to predict, experts at the national, state and local levels say the best approach for districts and boards is to cast politics aside and focus on understanding where these students come from, what services they need and how the education system can welcome them as assets.

These approaches often rely on officials being proactive by reaching out to students, their families and parents or guardians. “Because waiting for them to come to the school is more difficult in this time when you see everything on the news that is happening,” said Veronica Aguila, director of the CDE’s Migrant Education Program.

he term “model minority” was first used in 1966 by sociologist William Petersen in an article about Japanese American assimilation, and continues to persist based partly upon wide-ranging data showing that Asian Americans tend to hold higher degrees and earn larger incomes than the general population. For instance, a 2017 report released by the U.S. Census Bureau said that more than 55 percent of Asian Americans currently hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to just over 33 percent of the general population.

he term “model minority” was first used in 1966 by sociologist William Petersen in an article about Japanese American assimilation, and continues to persist based partly upon wide-ranging data showing that Asian Americans tend to hold higher degrees and earn larger incomes than the general population. For instance, a 2017 report released by the U.S. Census Bureau said that more than 55 percent of Asian Americans currently hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to just over 33 percent of the general population.

In reality, Asian Americans represent incredibly diverse communities with different ethnic, socioeconomic, historic and migratory characteristics. When taken as a whole, struggling groups within the population are rendered invisible. Take the example above, where it is cited that over 55 percent of Asian Americans currently hold a bachelor’s degree. Digging a little deeper produces a very different picture: only 14 percent of Laotian, 17 percent of Hmong and Cambodian, and 27 percent of Vietnamese Americans have a bachelor’s degree or higher. While 86 percent of Asian Americans have completed their high school education — slightly above the national average of 85 percent — Southeast Asian Americans have significantly lower rates. For example, 61 percent of Hmong Americans have completed a high school education.

well-respected research and policy expert described as “a giant in the world of education” by The Washington Post, Linda-Darling Hammond began her new role as State Board of Education President in February 2019 after Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed her to the body. The 11-person board oversees policy, academic standards, curriculum, assessments and accountability for the state’s K-12 public schools.

California Schools recently talked with Darling-Hammond about her vision for the state’s K-12 public education system, the need for greater funding and the persistent teacher shortage impacting districts up and down California.